Last week, Nick Thomas-Symonds, the UK’s minister for doing things with the EU, said that the new Labour government will seek to negotiate a “very ambitious” Sanitary and Phytosanitary Agreement (SPS, often referred to as a “veterinary” agreement despite the phytosanitary bit being about plants) agreement with the EU.

He expects serious negotiations to begin in early 2025. (h/t the BBC’s John Campbell.)

This is an idea that has been regularly floated by many people (guilty), but not always well defined.

For what it’s worth — other than a few battle-scarred Commission officials who probably won’t be involved — there’s a reasonable amount of enthusiasm on the EU side to at least entertain the discussion, perhaps because the UK’s own regulatory controls on imported EU food products are [finally] starting to bite after being delayed hundreds of times.

So, what is a veterinary/SPS agreement?

Well, ummmm, it depends.

The most comprehensive post-Brexit analysis has been carried out by Jun Du, Gregory Messenger, and Oleksandr Shepotylo in their April 2024 paper. And as they usefully demonstrate, there are many different types of agreements!

Rather than focusing on these, I think it is probably more useful to think about which trade barriers the UK wants to remove.

To massively oversimplify, if you want to export beef to the EU (ignore customs requirements etc), you must:

Be an approved establishment/producer, authorised to export beef to the EU

Get your beef checked out by a vet, who will provide an export health certificate that you will need to share with your EU buyer

Make sure your EU buyer has told the relevant EU Border Control Post that you’re going to be sending them some beef

Accept that your beef is going to be subject to document checks, identity checks and possibly intrusive physical inspection

Or, if you rather, in visual form:

All of which takes time, involves faff and costs money.

And why do these requirements exist?

Well, you have to be an authorised premises because the EU (and pretty much every other country which has some concern about food safety) wants some assurance that you’re not just selling meat out of your basement; a vet is needed to provide additional reassurance that the beef isn’t rotten, and then it all gets checked at the border to check once again that’s nothing wrong with the beef … and if there is something wrong to the EU wants to destroy it before it starts making people sick.

So, to get rid of **all**of these requirements the EU will need to be completely confident that the chance of dodgy UK beef being placed on its market is the same as if it was procured from within the EU.

In theory there are different ways to go about this, mainly involving people saying the word “trust” and “equivalence/mutual recognition” a lot, but in practice we know what the EU will ask for in the first instance:

Full UK alignment with relevant EU rules, as applied to domestic production AND imports [to ensure non-compliant stuff doesn’t slip in by the back door] and probably some sort of role for the ECJ in determining whether the rules have been applied correctly [in practice this could probably be designed in a way, a la the Withdrawl Agreement, where there is independent dispute settlement but on matters of interpretation of EU law the ECJ’s view has to be taken into account].

This is what people commonly refer to as the Swiss model when talking about an EU-UK SPS/veterinary deal. And … it could, in theory, remove all of the regulatory barriers mentioned above. But it would also constrain the UK’s ability to diverge from the EU’s SPS rulebook, and alter its SPS regime to accommodate the demands of other countries.

[Note: While the latter point would be an issue if the UK entered into negotiations with the US, the UK has so far managed to negotiate new FTAs with Australia and New Zealand and accede to CPTPP without diverging from EU SPS rules … despite Canada’s best efforts … so it’s clearly not **that** big of a deal.]

Buuuuuut, I kinda get the idea that, while the new Labour government isn’t into performative divergence to the same extent the past Conservative government was, it might find it difficult to accept these conditions in the first instance.

In practice, the government would probably [still] prefer an agreement that was a bit more accommodating of UK regulatory whims, even if it meant some of the barriers still remained. This is commonly referred to as the New Zealand model — New Zealand has an SPS deal with the EU that allows for simplified declarations, and a reduced frequency of physical inspections at the border, but doesn’t remove the need for products to enter via a border control post and be subject to the associated document and identity checks.

If this all sounds slightly familiar … it’s because it is.

During the TCA negotiations, the UK — half-heartedly — tried to negotiate an SPS arrangement based on similar principles to New Zealand. The EU said no, citing volumes of trade and the fact the UK wanted it to cover more products as a reason for concern.

This time things will be different?

Well, maybe. As above, the Labour government isn’t going to make a big song and dance about divergence to appease 30 hardliners in its party, so might be more willing to bind itself to EU approaches. On the EU side, in the coming months, there will be a reshuffling of people and they might be more willing to entertain some [really don’t want to overstate this … a little bit!] of flexibility in the context of a negotiation that also saw the UK accommodate EU offensive interests such as youth mobility and, yes, fish.

But it isn’t necessarily going to be easy …

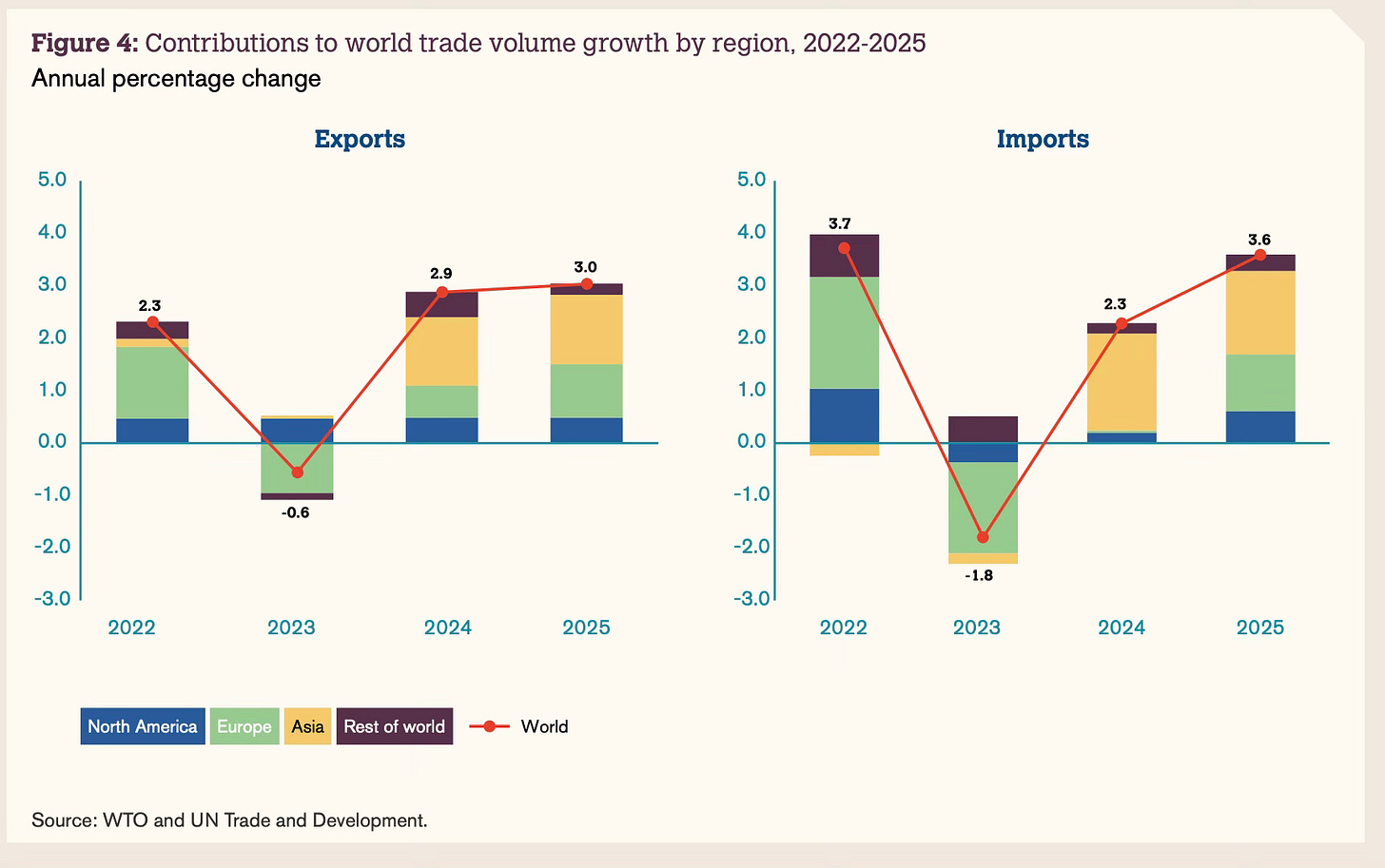

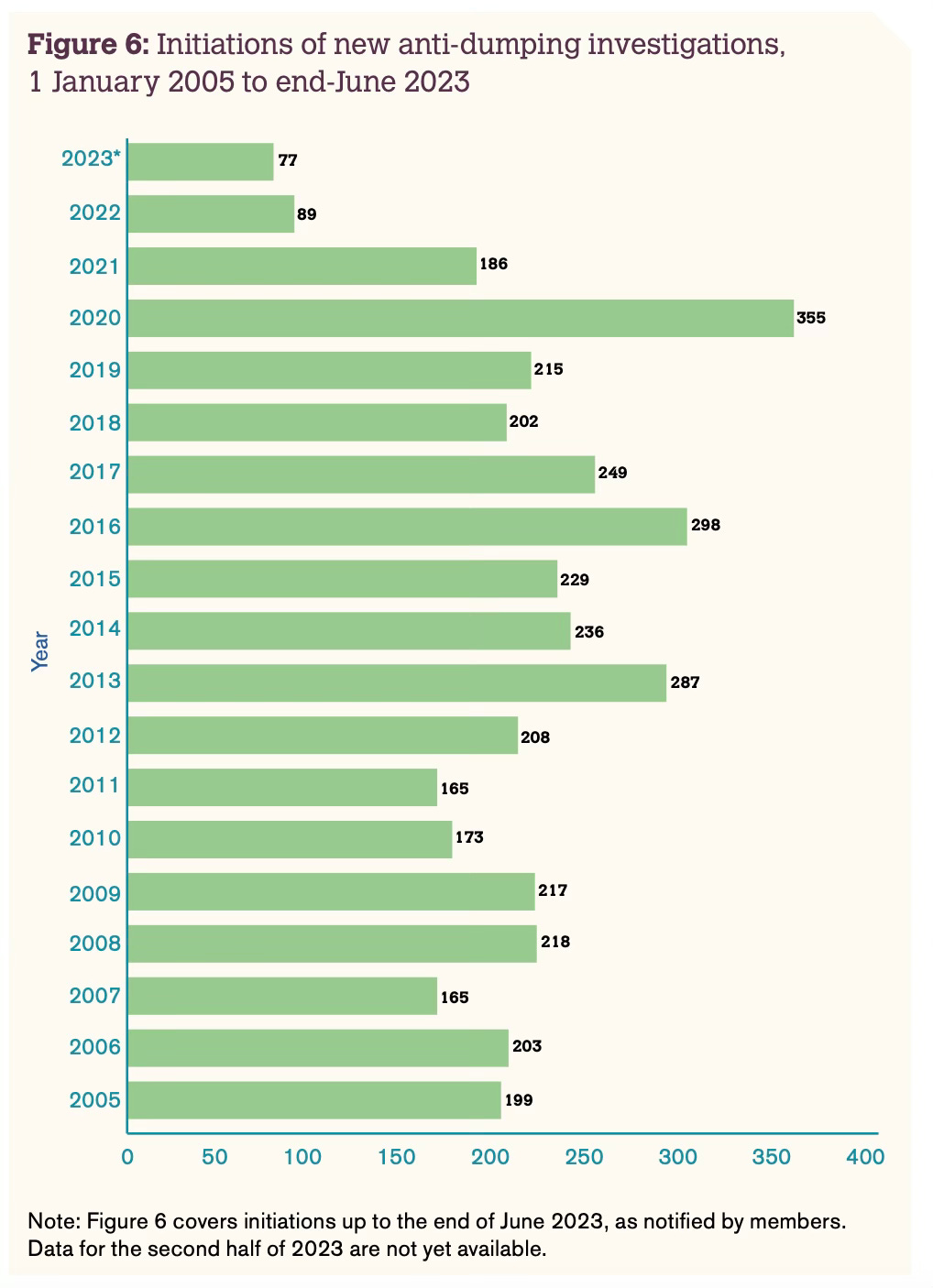

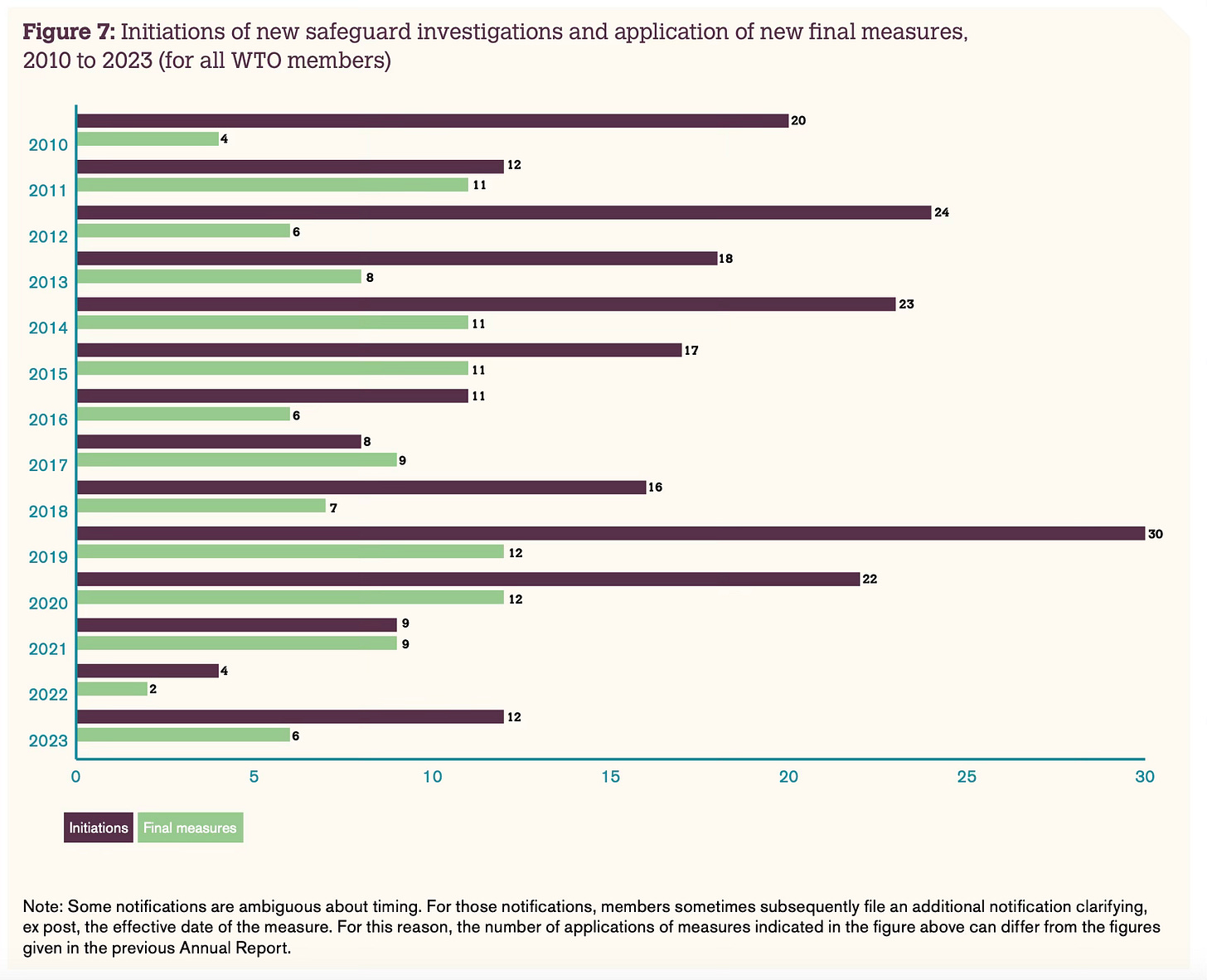

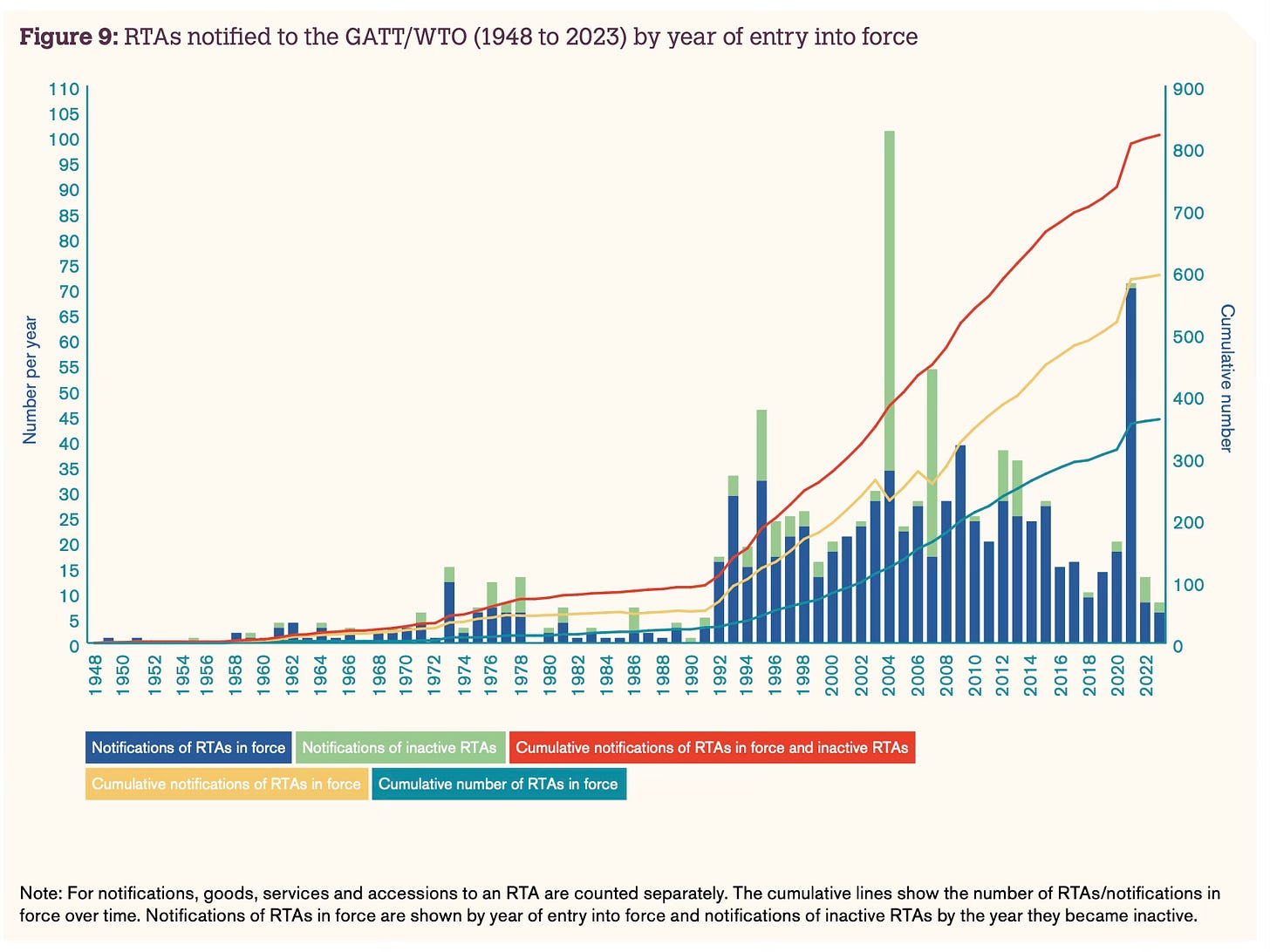

Charts of the week

All from the WTO’s 2024 Annual Report:

Best wishes,

Sam