CORRECTION: Most Favoured Nation: Breaking America

Why size matters, bees, weaponising transparency and censorship as a barrier to trade.

Welcome to the 59th edition of Most Favoured Nation. This week’s edition is free for all to read. If you would like to receive top quality trade content in your inbox every week, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber.

DUE TO BEING TIRED, THE FIRST VERSION OF THIS EMAIL HAD A VERY SILLY MISTAKE IN IT. THAT HAS NOW BEEN FIXED.

Scaling Up

The UK is a rich country. But with 67 million-odd people, it is still pretty small. And this is a problem if you are looking to grow a company. There are only ever going to be so many people interested in buying your stuff.

So what you really need is access to more people.

Take this Substack newsletter, Most Favoured Nation. Just over 3000 of you are free subscribers, and around 150 of you pay to receive it every week, which brings in around £5000 p/y (thank you!).

I am pretty pleased with this — it is not exactly like trade policy is something many people are interested in. As a proportion of the UK’s total population, about 0.004% are free subscribers, with about 0.0002% paying.

If I were to write the same newsletter for a US audience (population around 337 million), and a similar proportion of people subscribed, I would have 13,480 free subscribers, and 674 paid subscribers. In terms of revenue, I would be clearing about £25,000 per year.

You also see it with bands. Ed Sheeran isn’t sleeping on piles and piles of money because he had a few UK number ones.

Scale matters.

Or to put it differently, if you’re a company operating solely in the UK, you can make quite a lot of money. But to make loads and loads of money you’re going to need to find some more people to sell to.

China (1.5 billion people), India (1.4 billion), Indonesia (274 million) … there is a reason Western firms are trying to get a foothold in these markets, despite the numerous market access [and other] issues.

But it’s not always so easy to do.

The obvious market for UK companies, given the proximity, is the EU and wider-Europe (EEA countries, Switzerland, Turkey, etc.). And historically that has happened, to an extent, particularly in the manufacturing space. But for services in particular, Europe is tricky. Ignoring the different national regulatory approaches, cultural issues, and the fact the UK recently decided to make it more difficult for its companies to trade with the EU, language barriers can quickly shrink your potential market.

This newsletter, for example, requires the person to both be interested in trade policy and speak English. The EU has around 447 million people living in it, but [according to Wikipedia] only 51% of people are either native English speaking [13%] or have sufficient English skills to hold a conversation [38%]. Which reduces the potential market size to around 228 million. Still big … but no longer “America” big.

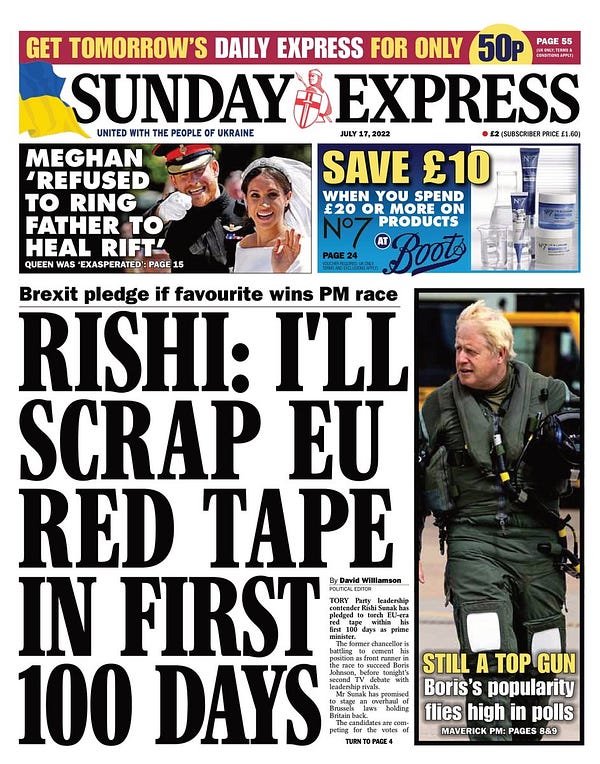

Anyway, where am I going with this. In the context of the fight to become the new Prime Minister, there’s lots of talk in the UK at the moment about regulatory innovation, divergence from EU rules, etc.. And y’know, maybe a sandbox-type environment will pull in some companies and investment that would not otherwise have happened. But as soon as companies want to go big, what the UK says and does in its domestic market just really isn’t that important.

But the UK’s trade, investment, education and language-learning policies really are. And it’s kinda annoying that no one appears to care that much.

Maximum Residue (Bees)

Back when I worked for an environmental NGO, one of the big issues concerning my colleagues was the plight of bees. This led to Europe-wide (relatively successful) campaigns to, among other things, curb the use of certain insecticides, particularly so-called neonicotinoids.

Occasionally someone would ask me something along the lines of “Can we stop the countries we import food from using neonics too?”

And the answer was usually something along the lines of “it’s complicated”.

The way trade rules generally work, is that any country can set rules laying out the conditions a product needs to meet to be sold on its market (subject to terms and conditions, such as not being overtly discriminatory against foreign things), but it is much much more difficult to constrain how products are made.

In the case of pesticides/insecticides and produce grown in the ground such as cotton, corn, cereals, sugar beet, and oilseed rape, this is usually dealt with via something called maximum residue limits. So restricted pesticides can be used to grow imported foods, but there are strict limits on how much of the pesticide “residue” can be present on the produce when it is tested. For some these are already set at near-zero (0.01 mg/kg), but others are benchmarked against international Codex Alimentarius standards, or take into account the practices of the specific country of-origin.

So for neonics, despite being restricted in the EU, some foreign farmers can still use them so long as there are only very small trace amounts left on the final product exported to the EU.

Anyhow, a new blogpost by trade and agrifood academic Alan Matthews argues that the EU has just thrown a “hand grenade” into this entire system.

In the Commission’s new draft regulation, it proposes reducing the maximum residue limit for two neonicitinoids, clothianidin and thiamethoxam, to the lowest possible trace amounts, effectively banning them.

Alan argues this is a hand grenade because:

The fact that the new MRLs have been set principally because of the impact of these insecticides on ecosystems in the exporting countries rather than to protect consumer health in the EU is one reason for comparing this notification in the title to this post to the equivalent of throwing a hand grenade into international agri-food trade.

A second reason is that neonicotinoid insecticides are the most widely used insecticides globally, with estimates suggesting they have a 24% market share. They are used in over 120 countries in more than 140 crops, including cotton, corn, cereals, sugar beet, oilseed rape, and others. Thus, the potential consequences of the new MRLs are very far-reaching (even taking into account that the proposed MRLs only cover two of the seven neonicotinoid insecticides in use globally today). Even if the restrictions can be justified, they are likely to cause severe disruptions to international trade.

Weaponised Transparency

Back during the EU-US negotiations for a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), the EU and US tried to negotiate the deal in relative secrecy. The texts were kept secret and even relevant MEPs were forced to read them in special reading rooms, with nothing but a pen and pencil for notes.

Anyhow, it didn’t work. The texts constantly leaked, largely via national parliaments and governments. And the whole secrecy thing was a pretty bad look, and allowed opposition campaigners to, let’s say, make things up about what was and was not going to be in the deal.

Since then the EU has learned its lesson and adopted a new approach: weaponised transparency. As we saw in the Brexit negotiation, it is now quite keen to publish (most of) the negotiation texts. Especially when it makes the EU look good.

On that note, here are (some of) the draft negotiation EU positions for its negotiations with India:

Censorship

We’ve covered before in MFN — highlighting the wonderful work of Nigel Cory — why censorship is the next frontier in international trade policy, particularly in the context of computer games:

Anyhow, the US International Trade Commission has now published a report looking at this very issue. As part of this report, it conducted a survey of American businesses, and their experience of censorship when trying to enter the Chinese market.

The survey finds:

Almost a quarter of U.S. media and digital service providers that were able to enter the Chinese market, representing more than half of the 2020 global revenue of all U.S. media and digital service providers active in China, experienced censorship- related measures.

U.S. businesses’ experiences with censorship were concentrated in certain industry sectors. It found that U.S. media and digital services providers were the most likely to have faced such restrictions. These companies include those that provide audiovisual content, such as movies and video games; and digital services and content, such as online platforms and computing services; as well as those that provide a combination of these products and services.

Almost three-quarters of U.S. media and digital service providers that experienced censorship were concerned about negative impacts on their operations in China, including their ability to provide products and services in China. Most also noted that censorship-related measures in China have become more challenging to deal with in the past few years.

Almost 40 percent of U.S. media and digital services providers that experienced censorship indicated that they had to self-censor to provide their products or services in China. As with censorship in general, this share was significantly higher for large U.S. media and digital services providers than SMEs in the category. Also, 12.7 percent of U.S. media and digital services providers that experienced censorship also experienced extraterritorial impacts from censorship-related measures and faced negative or mixed impacts to their products or services outside of China.

As ever, do let me know if you have any questions or comments.

Best,

Sam

Hi Sam - insightful and entertaining (still not sure now you do this) as always. I can perhaps simplify the MRL issue somewhat. The legal question is not how something is made. It is where the undesired harm would be caused. States are by default able to protect themselves, hence normal MRL regulation restricting imports containing residues that can cause harm to their people or environment. States are by default *not* able to protect people or the environment in other countries. There are exceptions, eg when this is agreed or otherwise results from international law (eg human rights, some public morals, environmental treaties, etc). But you need to find those exceptions, and in the absence of a neonicotids treaty or obligation it is just not there - unless you can argue that bees are a global concern, and hence of doemstic interest as well (an argument that can sometimes be made). So what does how something is made have to do with this? Well, sometimes it involves harms in the importing county (eg residues of chemicals dangerous at point of consumption). Sometimes it does not (residues of chemicals whose use is dangerous at the point of production but not consumption). And there can be overlap (chemicals harm the environment at point of production and consumption). The focus on how something is made can be a handy rule of thumb, but it is often misleading (it originates in the concept of a 'process and production method', a term which dates from 1970s negotiations on the Tokyo Round Technical Barriers to Trade Code, and which has taken on an unfortunate life of its own). Lorand

Another correction I'm afraid, India has official overtaken China to be the world's most populous country again. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/after-300-years-india-will-be-worlds-largest-country-again/articleshow/92875032.cms