CORRECTION: Most Favoured Nation: Much TRQ About Nothing

Tariff-rate quotas, digital tariffs, CBAM and why tariffs = electoral success

Welcome to the 125th edition of Most Favoured Nation. The full post is for paid subscribers only, but you can sign up for a free trial below.

One of the peculiarities of the Windsor Framework (WF), formerly known as the Northern Ireland Protocol, is that it inadvertently prevents importers in Northern Ireland from using UK or EU tariff-rate quotas.

The problem stems from the design of the WF. Despite the EU’s tariff regime applying to rest of world imports into Northern Ireland as default [sorry, people who pretend otherwise, this is just true], authorised Northern Irish importers can use the UK tariff so long as — amidst other conditions – the difference between the applied EU and UK tariff rate is less than 3 percentage points.

For example, if the EU tariff was 50% and the UK tariff was 40%, I would need to use the EU tariff because the difference between the two, 10 percentage points, is more than 3 percentage points. However, if the EU tariff was 2.5% and the UK’s was 0%, I could use the UK tariff because the difference, 2.5 percentage points, is less than 3 percentage points.

Cool.

However, this system wasn’t really designed with tariff-rate quotas in mind.

[To re-cap, a tariff-rate quota allows a fixed quantity, say 1000 tonnes, of a product to be imported at a lower tariff rate within a set time period.

For example, 198 tonnes (product weight) of New Zealand High Quality Beef can be exported to the United Kingdom at a 20% ad valorem duty every year. Product imported outside the quota is subject to an out-of-quota tariff rate of 12.0% + 118.0 - 254.0 GBP per 100kg/net.]

“What is the problem?” I hear you ask.

Well, the issue is that the EU and UK never agreed on whether the 3 percentage point difference should be assessed against the in-quota, or out-of-quota, rate.

This is perhaps easier to explain with another example …

The UK and the EU both have an identical tariff-rate quota on New Zealand lamb. This tariff-rate quota allows UK buyers to import 102,620 tonnes of sheep meat tariff-free each year; the EU equivalent allows EU buyers to import 125,769 tonnes of sheep meat tariff-free each year.

So you might assume that a Northern Irish importer would be able to compare the UK’s in-quota rate, 0%, to the EU’s in-quota rate, also 0%, and therefore import Kiwi sheep meat tariff-free. Wrong. In practice, the UK importer has been required to compare the UK in-quota rate, 0%, to the EU out-of-quota rate 12.8% + 90.2-311.8 Euro per 100kg/net … which has a significantly larger tariff differential than 3 percentage points.

Why can’t the Northern Irish importer just use the EU tariff-rate quota instead? Because in 2020 the EU passed legislation prohibiting Northern Irish importers from using EU tariff-rate quotas.

BUT THIS HAS ALL [WELL, PARTLY] BEEN FIXED.

This week, as part of the UK’s efforts to convince Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party to stop blocking the formation of a Northern Irish government, the UK and EU agreed to do something about the tariff-rate quota problem.

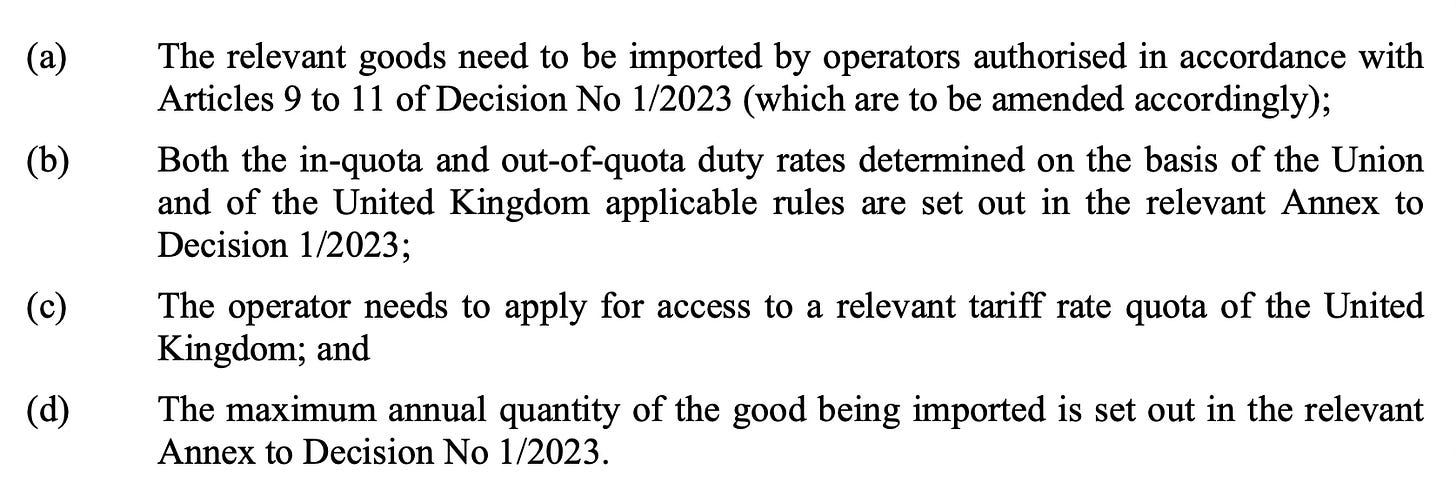

Subject to the following conditions, Northern Irish importers will, once this is all formally signed off, be able to use some UK tariff-rate quotas:

This is initially slightly amusing when you consider that some Northern Irish farmers could conceivably have liked the existing situation whereby their exports exploited tariff-rate quota arrangements benefiting the UK, but they did not have to worry about reciprocal competition from foreign products entering Northern Ireland.

[Correction: It has been pointed out to me that the UK FTA tariff-rate quotas are indeed included, for example, the UK-Australia beef tariff-rate quota [see: quota order number 05.4970], so I have deleted and amended some of the commentary below.]

However, upon further inspection it becomes clear the new measure does not apply to ALL UK tariff-rate quotas — for example, I don’t think fungible goods such as sugar are included (unless I’ve missed it!).

And, when you look through the list of applicable tariff-rate quotas in the Annex to the decision, you can see that it covers either TRQs where both the UK and EU tariff-rate quotas are the same or, in the case of tariff-rate quotas in new UK free trade agreements, such as Australia and New Zealand, products such as lamb and beef where the EU also has some comparable, limited, zero-rated tariff-rate quotas in place too. it becomes obvious that it mostly covers only those where the UK and EU tariff-rate quotas are pretty much identical. (Note: in the case of the new UK FTA tariff-rate quotas that do not directly match up to EU alternatives, there is also some wider product coverage, e.g. processed beef and their existence arguably means the maximum volume threshold is higher than it might otherwise have been.) There are also fairly conservative limits on the maximum amount of product that can be imported into Northern Ireland each year, which guards against a big uptick in imports.

So while Northern Irish importers can access some of the new UK free trade agreement tariff-rate quotas, the quantities are limited.

Or, to put it another way, Northern Irish importers will still not be able to directly access the new, very generous, UK tariff-rate quotas offered to Australia under the new UK-Australia free trade agreement.

This all seems to make sense from an EU risk-management perspective and looks like a sensible compromise. And, as above, I’m not sure even the most unionist Northern Irish farmer minds if some limits remain on the amount of Australian food products able to enter the Northern Irish market.

Digital duties

The WTO's 13th Ministerial Conference (MC13) will take place from 26 to 29 February 2024 in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. As is the case every time this happens, companies are worried that the current moratorium on placing customs duties on cross-border data flows will not be extended. Opposition to the extension comes, as usual, from the likes of South Africa, India, Pakistan, Indonesia, etc.

Occasional MFN contributor, George Riddell has written about it for us previously here:

Most Favoured Nation: Whither the WTO Moratorium on Customs Duties for Electronic Transmissions?

Welcome to the 109th edition of Most Favoured Nation. This week’s edition is free for all to read. If you enjoy reading Most Favoured Nation, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

In the run-up, 175 organisations have written a letter saying they want the moratorium extended.

I suppose the big concern this time is that, given the US’s shenanigans elsewhere in respect of the e-commerce negotiations and the withdrawal of its support for prohibiting forced data localisation and forced transfer of source code, the Americans might not be as willing to help get the extension over the line.

I don’t *think* the US will torpedo the moratorium as well, but it is interesting to note that in recent years it is the EU, of GDPR and cross-border restrictions on the free flow of data fame, that seems to be pushing ahead with a pro liberalisation digital trade agenda (as well as the UK, Singapore, Australia and Japan).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Most Favoured Nation to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.