Before we get on to discussing one specific element of the new UK-US “trade deal”, I’d like you to imagine that the company you work for decides to post you abroad for a few years.

You are being sent to open a new office in *insert foreign country*. Your visa conditions stipulate that you can work there for a maximum of three years before needing to come home. You have no intention of living there for longer than that. While working there, you will continue to pay social security (or equivalent) payments in your home country.

Given that you don’t want to live permanently in the place you’ve been temporarily posted to for work … Given that you will never draw down a pension in the country you’ve been temporarily posted to for work … Given that, as above, you are already paying into the system in your home country …

Is it at all fair for the country you are temporarily posted to to ask you to pay into a system that will never pay out?

Answer: No, obviously.

But lots of people in the UK have decided to be performatively ignorant to score political points.

At least, that’s the only obvious interpretation of these reactions to, as part of a new free trade agreement, the UK agreeing to negotiate a new double contribution convention with India:

Because, yeah, it’s really not a big deal. (And applies in both directions!)

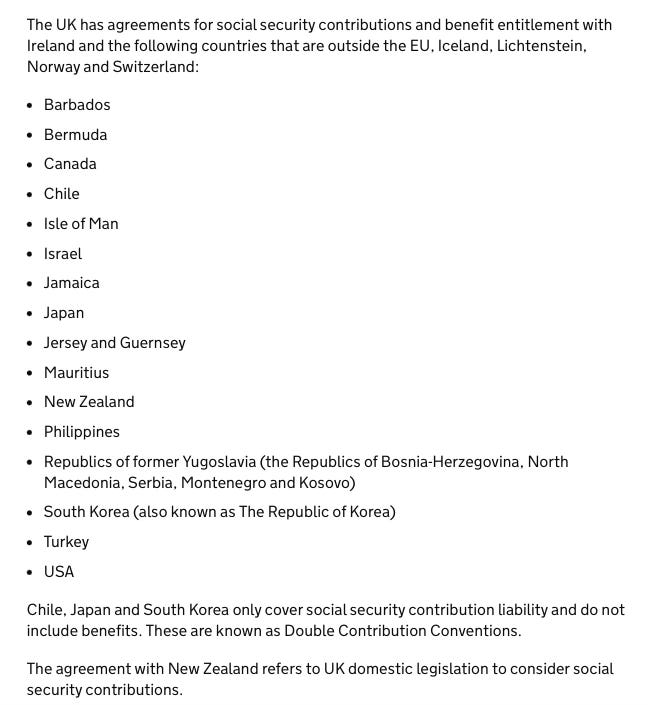

Here’s a list of all of the equivalent agreements the UK already has:

If you’re interested in what this type of agreement actually says, here’s the 2020 implementing legislation for the UK-Japan DCC. (Those of you who read the small print will note the exemptions last for five years, rather than the three reported for India.)

Anyway: Not. A. Big. Deal.

This is also slightly annoying because my initial plan for this newsletter was to moan about the fact that the UK and India announced a free trade agreement and then promptly decided to provide next to no detail on key aspects.

For example, we know that India has agreed to create a tariff-rate quota for UK car exports, offering a fixed annual number the lower tariff of 10%. However, what we don’t know is what the annual size of this quota is, how the quota is going to be managed, whether it will be first-come-first-served or some other mechanism, what the rules of origin for the cars are, etc. Basically, all the information a person like me needs to determine the extent to which this new market access is beneficial to UK exporters.

But yeah, the social security stuff annoyed me more.

Art of the Deal

Here are some random observations about the UK’s “deal” with the US. (I put “Deal” in quotation marks because it’s more of a statement of intent with some questionably binding legal commitments up front.)

Not bad. From a UK perspective, the government is probably pretty pleased with the outcome. The US has agreed to reduce its tariff from 25 per cent to 10 per cent for 100,000 UK car exports every year. The US has also agreed to create a new quota for UK steel and aluminium, and be nicer to the UK when imposing future national security tariffs on pharmaceuticals and other products [Ed: let’s see …]. In return, the UK gave the US … not very much. The UK didn’t fold to US pressure to change its food regulations, didn’t scrap its digital services tax, didn’t do … really anything particularly difficult to sell domestically. Instead, the UK has committed to lowering some tariffs on a fixed quantity of beef and ethanol and negotiating on further tariff reductions and digital cooperation.

Tariff-rate quotas. As above, the thing about tariff-rate quotas is that the benefits can depend in large part on how they are managed. For those of you with an interest in the US’s general approach, read all about it HERE. From memory, the previous steel quota (mentioned again below) was administered on a quarterly basis, first-come-first served.

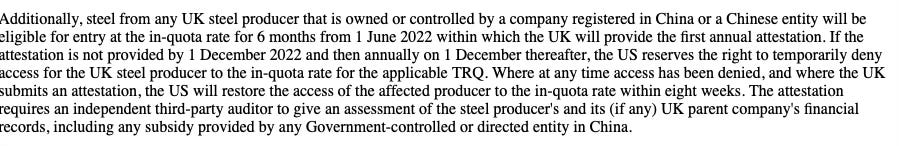

China. A subtext to the US-UK deal and subsequent negotiations is that the US will impose conditions on any UK exports to the US granted tariff relief to ensure China-linked exports don’t benefit. In addition to strict rules of origin — “to ensure U.S. and UK firms can benefit from these changes in practice, both countries intend to apply rules of origin that maximize bilateral trade and prevent non-participants from using our bilateral arrangement to circumvent tariffs” — the agreement also refernces “supply chains security requirements” with a focus on the “nature of ownership of relevant production facilities”.

On this point, it is worth reviewing the previous Biden-era US-UK deal, which partially removed the Trump 1.0 steel tariffs:

Not the end. Like, this isn’t over. It’s a reprieve, for now. For one, the “deal” itself commits to more negotiations, but also, Trump could change his mind, the US will come back for more concessions if and when it imposes tariffs on pharmaceuticals, films, etc.

MFN not yet dead. One of the things worrying trade nerds the most is that in accommodating Trump, countries will breach their Most Favoured Nation obligations and set a precedent that ultimately leads to the unravelling of the rules-based trading system. I wrote about it previously in a piece hilariously titled Most Favoured Nation is Dead. (Funny, because this newsletter is in fact called Most Favoured Nation. Ho Ho.) The announcement of the UK deal has upset these people, because it looks like the UK has done a bit of this, i.e. through saying it will open up new quotas on beef and ethanol specifically for the US.

Buuuut, I think people might be overreacting slightly. For one, we still have no idea what legal form this deal will finally take — it’s currently just a piece of paper with words on it. It might end up actually being a free trade agreement! (Heh.) But also, even if the UK does do a little bit of rule bending, is it any worse than what countries did last time when they, for example, when Japan did a mini-deal with Trump, the EU dropped tariffs exclusively on the species of lobster native to North America to accommodate Trump, or in 2019 when the EU tweaked its tariff-rate quota for beef to allocate a bigger proportion to the US? (Yes, I remember EVERYTHING.) Not so sure.

Big on YouTube

A few weeks ago, with much trepidation and a plea that he wouldn’t mock me, I agreed to be interviewed by a YouTube personality for a video he was doing on international trade.

Anyway, here it is, and nearly one million people have already viewed the video. The internet, man.

The Lord’s work

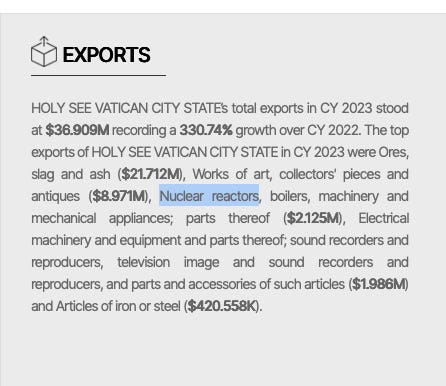

Given recent events, I decided to look up the Vatican’s main exports. And folks, I have some questions …

Chart of the week

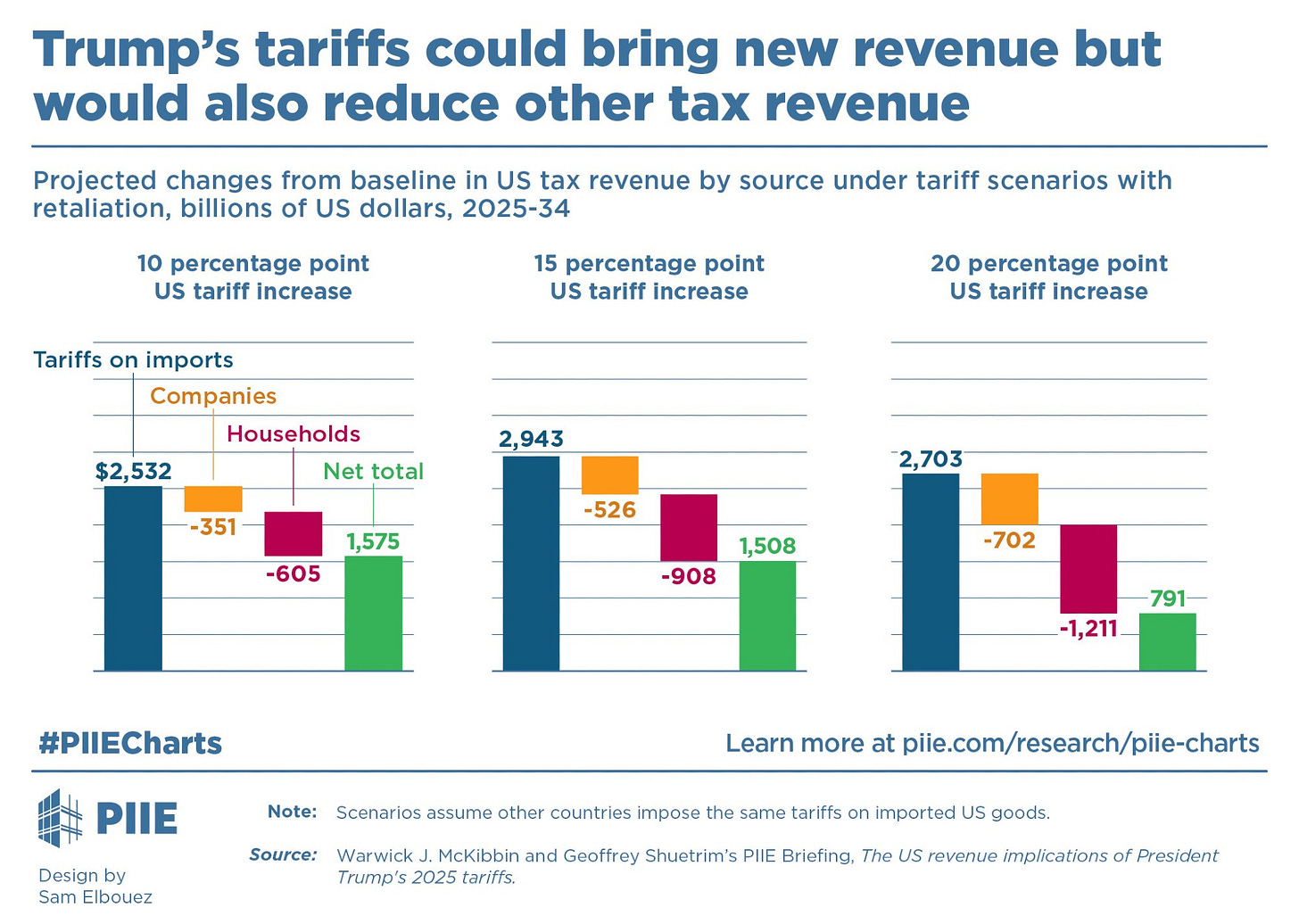

I’m quite enjoying the new sport of trying to work out how much money Trump’s tariffs might raise. Here’s a new effort by PIIE:

Best,

Sam