Last Friday, the UK’s Trade Remedies Authority (TRA) recommended that the UK revoke existing anti-subsidy and anti-dumping on imported Chinese e-bikes. The anti-subsidy tariffs currently range from 3.9-17.2%, the anti-dumping tariffs from 10.3-70.1%.

Long-term readers will know that I quite like writing about the TRA, which in its own way has been responsible for quite a few political scandals — see here and my attempt to explain how the TRA toppled Boris Johnson’s premiership here, for example.

And here, again, in its own little way, in a world where tariffs and protecting local producers are the name of the game, the TRA has done something slightly controversial: it has determined that consumer interests (as defined by them) are more important than producer interests (as also defined by them).

The relevant finding — the so-called Statement of Essential Facts — for both the anti-subsidy and anti-dumping measures can be found by clicking through the relevant case files listed on this page.

In summary, the TRA determined that if the tariffs are lifted it is probable that the subsidisation of e-bikes would recur [emphasis added]:

In accordance with regulation 99A(1)(a) of the Regulations we assessed whether

importation of subsidised goods subject to review would be likely to continue or recur if a countervailing amount was no longer applied (the likelihood of subsidised imports assessment). We determined that it is likely, on the balance of probabilities, that subsidisation of the goods subject to review from the PRC would recur if the measure were no longer applied.

And that the subsidisation would cause injury to UK producers:

18. In accordance with regulations 99A(1)(b) of the Regulations, we considered whether injury to the UK industry in the relevant goods would be likely to continue or recur if the measure were no longer applied (the likelihood of injury assessment). We determined that it is likely, on the balance of probabilities, that injury would recur if the measure were no longer applied to the goods subject to review.

The TRA reached the same conclusion in its review of the anti-dumping tariffs too.

So, given the TRA found evidence that unfair subsidisation and dumping would probably recur, absent the tariffs, and that this would harm UK producers, why is the TRA recommending that the tariffs are scrapped?

Answer: the Economic Interest Test (EIT).

The EIT is the third pillar of the TRA’s assessment, and, in addition to assessing the impact of tariffs on UK producers, it allows the TRA to consider the potential impact of tariffs on consumers, geographies and “other matters we [the TRA] considers relevant”.

In the context of this investigation, the EIT has led to the TRA netting off the positive impact of the trade defence tariffs for UK producers (well, in reality mainly one single UK producer of folding e-bikes) against the negative impact of the tariffs on UK retailers and consumers.

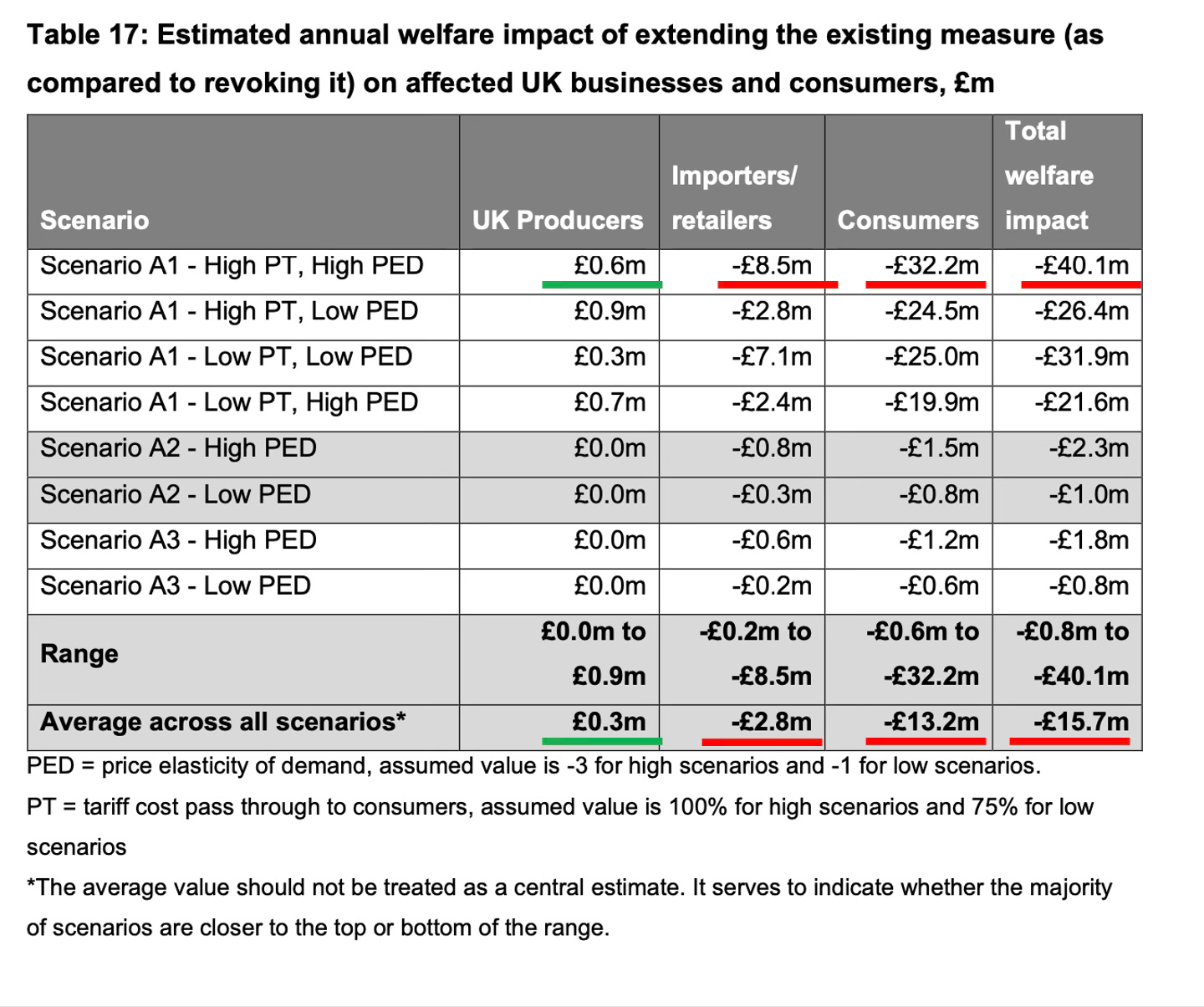

In the table below I’ve underlined the positive impact of the anti-subsidy tariffs in green and the negative impacts in red. Across the different scenarios, the TRA has determined that retaining the anti-subsidy tariffs would result in a net welfare loss of £ 15 million. In the most severe scenario, the welfare loss would top out at £40.1 million.

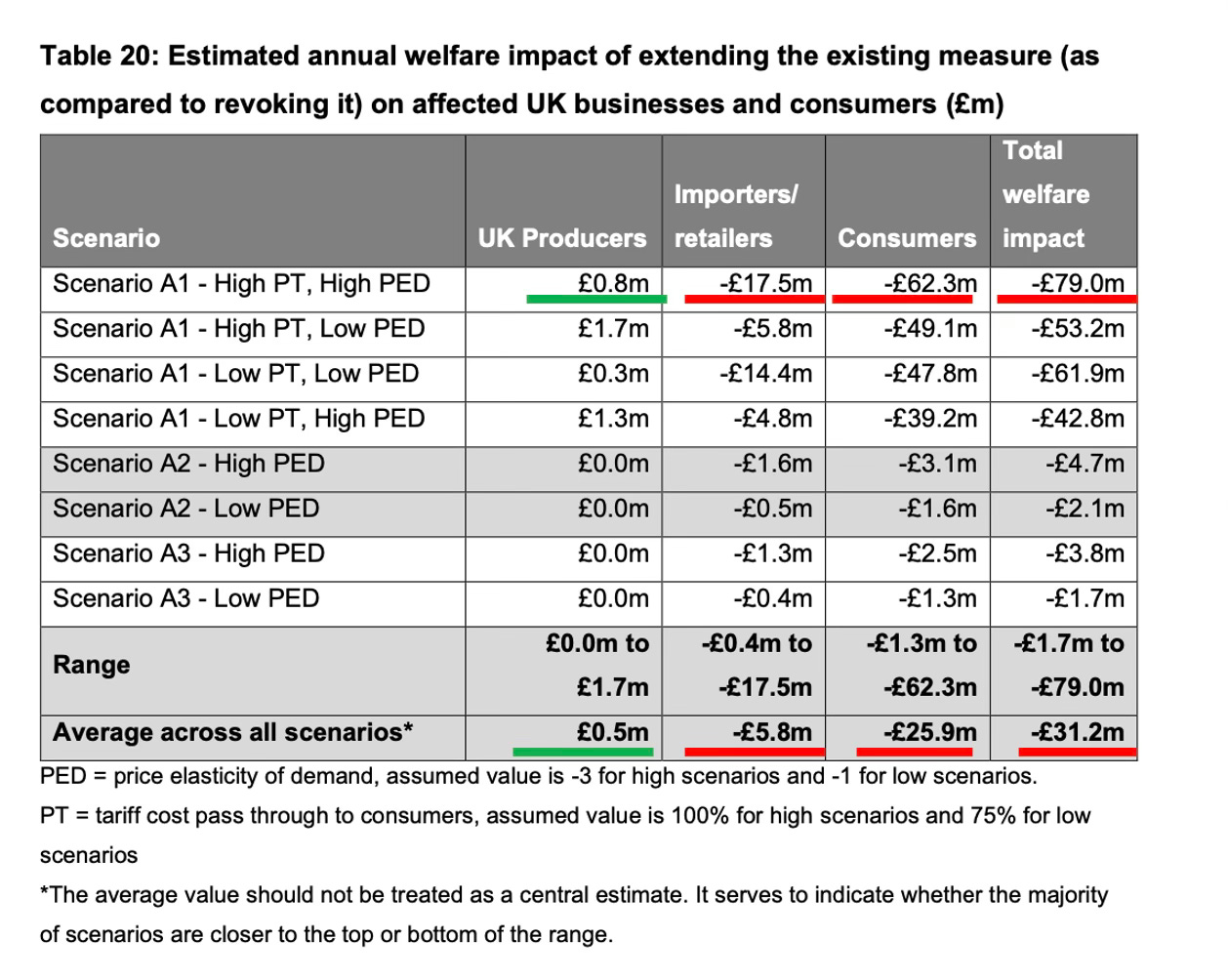

Applying the TRA’s EIT to the anti-dumping tariffs, which are higher, produces an even larger average welfare loss of £31.2 million, topping out £79.0 million.

In summary, according to the TRA’s calculations, unfair Chinese trade practices will damage UK e-bike producers, but the consumer benefits are significant so, therefore, it is in the UK’s overall interest to scrap its trade defence tariffs.

In the context of wider global trends, where the emphasis has shifted away from consumers with a near-exclusive focus on producer interest, this is a brave recommendation!

But will it fly?

Re: the e-bikes case, the TRA has given itself an easy way out. Alongside its central recommendation of scrapping the tariffs entirely, it has also presented the option of limiting the tariffs to folding e-bikes, therefore providing some ongoing protection for the main UK producer of e-bikes.

I expect this is what will happen.

But the TRA’s application of the EIT, and the forthcoming government/industry reaction, have some wider ramifications for UK trade policy.

For example, if the UK does copy the EU’s investigations into imported Chinese electric vehicles, it is quite possible that the TRA’s EIT would throw out a similar recommendation: some producer harm netted off against significant consumer benefit. But this might not be the answer that the government wants.

So what then?

In that case, perhaps it is (from a political perspective) better to have a fight over the legitimacy of the TRA’s application of the EIT in relation to e-bikes now, when it is fairly low salience, rather than later when it could cause more significant problems.

I suspect this won’t be the last time I write about this.

Best wishes,

Sam

Typically excellent Sam, thanks. Excuse the basic question but could this be a process we may see re Chinese EVs? Could the TRA come to the same conclusion - that they benefit the consumer (in simple terms)