With many thanks to EY’s George Riddell for covering last week (and using the opportunity to start a fight over Mode-5 services), I’m back.

Embracing aurtarchy

The world is a scary place.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led many governments and businesses to revisit the assumption that economic liberalisation and openness to trade will make the world a more harmonious place. Now, all we hear about are the dangers of becoming over-dependent on countries that are not to be trusted.

These discussions usually get to a place where people start talking about trading/political blocs, usually broken down into three crude categories:

The democratic bloc: Centred on the US, members include the EU, UK, Japan, South Korea, etc.

The authoritarian bloc: Centred on China, members include Russia, Belarus, etc

The unaligned bloc: This is where you put countries that don’t neatly fall into either of the other two blocs, but do their best to stay on good terms with both. Think the Gulf states.

The frustrating thing about these kind of conversations is that it is usually taken as a given that the US will happily sit in the middle of the democratic bloc, bequeathing economic benefits and market access to those countries that get on side. And while it is true that for this power-bloc system to work the US needs to be at its centre, I do wonder whether the US itself is all that up for doing so.

Because, to put it bluntly (at least from a trade perspective), we all need the US a lot more than the US needs us.

There are different ways of measuring this. One way is to look at total trade (imports plus exports) as a percentage of GDP. The lower the percentage, the less reliant your economy is on the rest of the world.

As you can see from the chart below, at around 23% US total trade as percentage of GDP is one of the lowest in the world. The only countries (for which we have data) with a lower proportion are Cuba and Sudan … for very different reasons. The OECD average is around 50%, while the EU average is up around 85%.

There are of course issues with this approach: for example a small percentage of a very large number can still equal a lot of trade. It also doesn’t tell you exactly what is being traded — for example, it is possible that total trade is not a huge relative to a country’s total economy, but the main thing it imports is drinking water … which is pretty important.

But still … I think it tells an interesting story. And that story for me is that the US is pretty much the only developed nation that could go close to full autarchy without completely blowing up its economy. Like, it would be poorer than it would be otherwise, but it’d probably be fine. Which … y’know … makes me wonder as to whether its political incentives vis-a-vis openness and trade are quite the same as all the countries relying on it.

If you appreciate the MFN content, and would like to receive MFN in your inbox every week, please consider signing up to be a paid subscriber.

There are a number of options:

The free subscription: £0 – which gives you a newsletter (pretty much) every fortnight

The monthly subscription: £4 monthly - which gives you a newsletter (pretty much) every week and a bit more flexibility.

The annual subscription: £40 annually – which gives you a newsletter (pretty much) every week at a bit of a discount

If you are an organisation looking for a group subscription, let me know and we can work something out

Trade barriers are bad for [small] business

Thomas Sampson and co. at the LSE have published a new paper looking at the impact of Brexit on the UK’s trade with the EU relative to its trade with the rest of the world, with a focus on around 1200 products.

As you’d expect, UK-EU trade has been negatively impacted. But not quite as everyone expected: UK relative imports from the EU have fallen by about 25%, but UK exports to the EU have held up just fine.

Or have they?

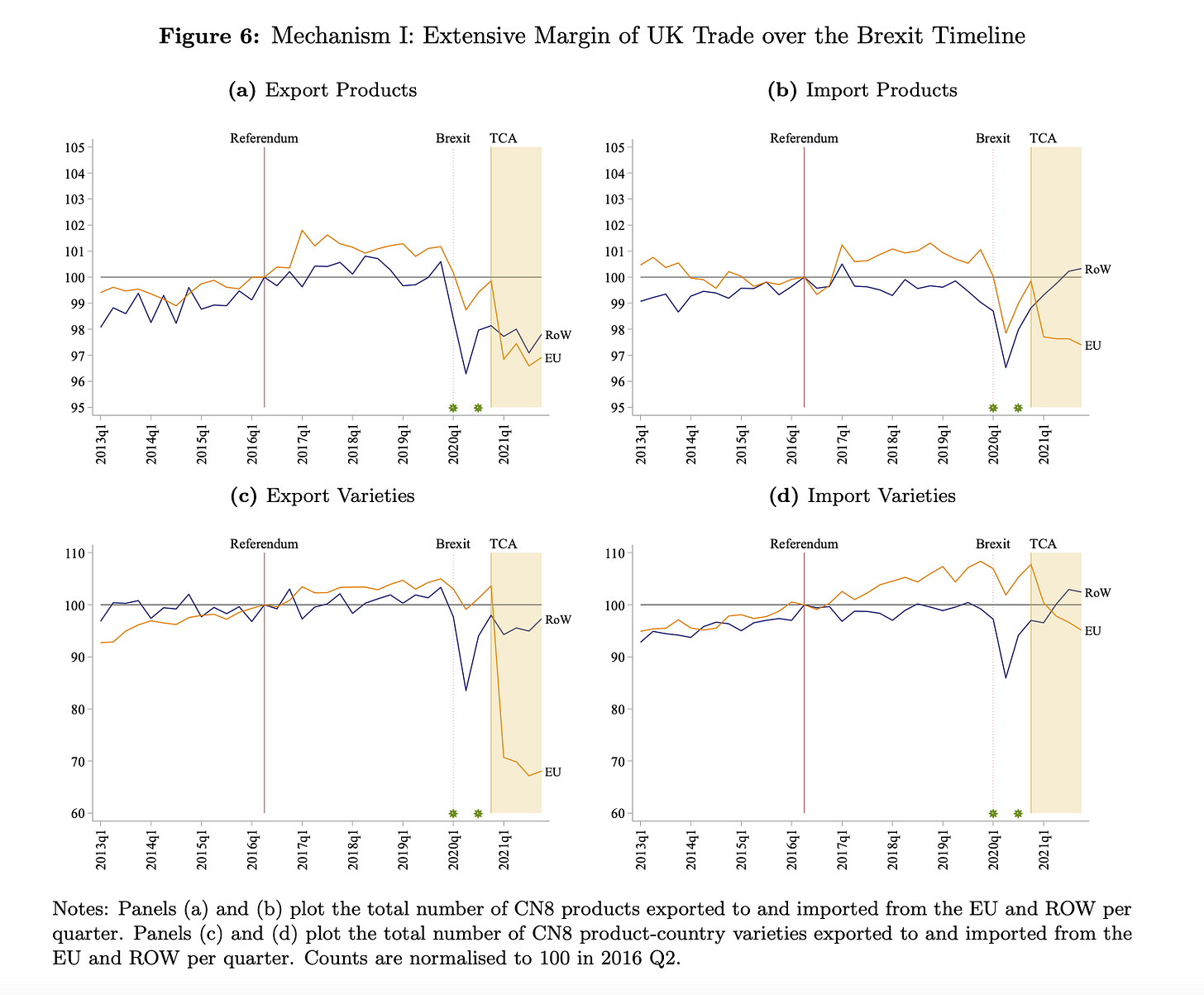

The paper’s most interesting finding is that while exports have held up at the aggregate level, the variety of goods being exported has fallen dramatically [see Figure 6 (c)]:

In their own words [my emphasis]:

Nevertheless, the start of the TCA led to a large and persistent drop in the extensive margin of relative UK exports to the EU, as measured by the number of observed export relationships. The estimates imply that the TCA has reduced the number of 8-digit product-country varieties exported to the EU each quarter by around 30%, and this contraction is driven by the destruction of low-value trade relationships. Consequently, it would be a mistake to interpret the missing export value effect as evidence that UK exporters were unaffected by the introduction of the TCA. Instead, we conjecture that the TCA has increased the fixed costs of exporting to the EU, causing small exporters to exit small EU markets, but not (or at least not yet) severely hampering exports by large firms that drive aggregate export dynamics.

Fertiliser.

Food is getting more expensive. One of the reasons for that is the cost of fertiliser, which is currently very expensive due to high energy prices [the main reason imo], Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and sanctions on Russian and Belarusian potash exports.

But Russia isn’t the only country at fault. New research by (MFN fan favourite) Chad Bown and Yilin Wang of the Peterson Institute makes the point that Chinese export restrictions are also a big part of the story:

The only thing I’d add is that, for a full picture, we should remember that Russia also started restricting fertiliser exports prior to invading Ukraine, in November 2021. So something like this:

It’s also fairly difficult to determine cause-effect. While export restrictions are certainly making the issue worse, in the first instance at least they look very much like a reaction to high fertiliser prices (caused by gas becoming more expensive) rather than the cause.

That’s it for this week. Next week, paid subscribers will be treated to an in-depth discussion on the legal shenanigans of the UK’s sugar industry. If that sounds up your street (and why wouldn’t it?), please do consider paying up.

Best wishes,

Sam

Trade is a difficult idea for those who are interested in studying geopolitics. Over the lifetime of MFN I’ve come to appreciate that Sam is a pragmatist par excellence, a true solution provider. Essential for a trade operative. However, when one looks at the geopolitics of US autarky historically in relation to the rest of the world one quickly bumps up against the reasons for the US position re the GDP export/import realities of much of the rest of the world. Perry Anderson, Chossudovsky, Engdahl, Diana Johnstone, Blum, all from differing perspectives show us why the world is where it is today.

China, Japan, S.Korea, Malaysia etc. all played the WTO game and grew their economies dramatically. According to these countries no trade barriers is a good thing if you use that advantage to your advantage.

The UK seems to have an economics establishment that is internationalist and ideological. It does not think in terms of "how can I help my neighbours here" but instead floats somewhere over the Atlantic with one foot in the EU and the other in the USA.

The EU and our recent trade agreements have been an unmitigated disaster for the UK. See https://therenwhere.substack.com/p/the-economics-of-brexit