Most Favoured Nation: Dirty Money

Money laundering, processing trade, e-commerce moratoriums and digital protectionism.

Welcome to the 53rd edition of Most Favoured Nation. In a slight scheduling change, MFN will now arrive in your inbox at the beginning of the week, rather than the end. Otherwise, as you were.

Let’s say you’re a big ol’criminal. And a wealthy one at that. Everyone is buying your drugs, guns, whatever. But the problem is everyone knows you are a criminal. No bank will touch you. Your bank notes are grubby. And the police are constantly sniffing round your legitimate businesses looking for a reason to shut them down.

You might be a cash millionaire. But spending that money ain’t easy. Buying anything normal people want such as cars, houses, private school places, yachts and the like requires you to, I am led to believe, pay someone who looks like Jason Bateman quite a bit of money to set up shell companies, bribe and blackmail law officials, and launder your money through an assortment of floating casinos, strip clubs, motels and dodgy constructions companies. [My research for this piece may have exclusively involved watching the Netflix show Ozark.]

So how much is £100 actually worth if you’re a criminal? Probably not £100. Reliable sources in the criminal underworld (I joke I joke, I mean accountants) tell me that £100 in dirty cash is really worth around £80 in real money, once you take the costs of cleaning it into account.

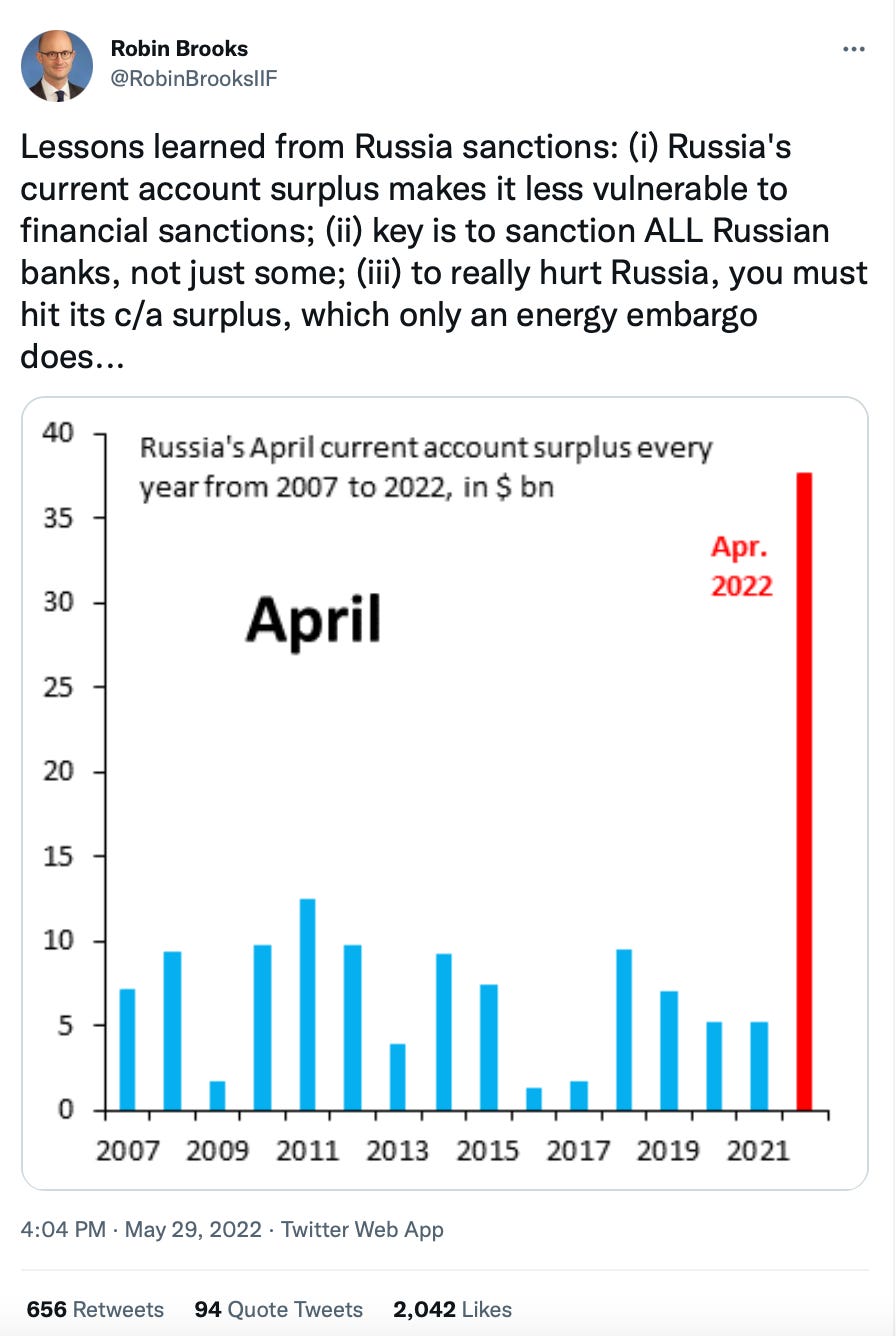

Anyway, that’s the convoluted backstory as to why this tweet by the IIF’s chief economist Robin Brooks slightly irritated me:

Because all this chart actually tells us is that Russia is exporting a lot more than it is importing (crudely speaking a current account surplus mainly means exports > imports). But this is … kinda obviously what was going happen? Much of the West put restrictions on exports to Russia, but continued to buy Russian energy. So imports down, exports the same or higher = bigger current account surplus.

And the early evidence suggests that Russian imports really have taken a hit:

Source: Author’s calculations, relevant national statistics bodies (2022)

Due to the myriad export restrictions, financial sector sanctions and voluntary withdrawals from the Russian market, even the best case scenario for Russian importers buying non-sanctioned products such as food and medicines is that their cash gets treated like a Scottish £10 note in London. Technically legal tender, but no one really wants it.

The worst case scenario for Russians trying to buy restricted products such as semiconductors? You’re no different from a drug lord trying to hand off your gym bag full of crumpled up notes.

So yes, a big current account surplus means that Putin is now sitting on mountains of foreign cash. But the fact he is sitting on a mountain of foreign cash suggests … well … that he’s having trouble spending it.

And while, I suppose, a pile of cash/paper could be a tiny bit useful in its own right as a bed or something, in reality, if you can’t use the money to buy things you need – in Russia’s case military equipment and things used to make military equipment – then it’s really not worth that much at all.

So what’s Putin’s pile of foreign cash actually worth in the real world? 15 per cent less? 20 per cent less? More?

Of course, as with the drug lords, Russia will work out how to get some of the things it needs. The whack-a-mole that is circumvention and counter-circumvention will become a monthly news item.

But as of now it appears Russia is struggling to do so. Note the fall in Chinese imports from the peaks of late 2021 that coincides with the steep falls from sanctioning countries. But for me this is the thing to watch: what is Russia buying, from where, and in what quantities?

Because otherwise Putin is just sitting on a big pile of useless paper.

Anyway for more on this discussion, Matt Klein, and the response from Robin Brooks, is well worth reading. As you can probably tell, I lean Matt’s way:

If you appreciate the trade content, and would like to receive MFN in your inbox every week, please consider signing up to be a paid subscriber.

There are a number of options:

The free subscription: £0 – which gives you a newsletter (pretty much) every fortnight

The monthly subscription: £4 monthly - which gives you a newsletter (pretty much) every week and a bit more flexibility.

The annual subscription: £40 annually – which gives you a newsletter (pretty much) every week at a bit of a discount

If you are an organisation looking for a group subscription, let me know and we can work something out

Trust the process (GVC 2.0)

DG Trade’s Lucian Cernat has a new ECIPE paper out looking at the impact of so-called ‘processing trade’. Unknown to all but customs nerds, most countries have customs procedures that allow firms to more readily participate in global value chains by allowing them to claim back the duties paid on imported components that are then incorporated into exported goods.

Sometimes this happens in freeports or freezones, but quite often places with more modern customs rules such as the EU and UK allow firms to make use of a procedures called something like “inward processing relief.” Something like this:

Anyway, a bit like the fact that many countries don’t actually levy tariffs on imports valued beneath a certain threshold, these customs procedures go largely ignored in most discussions about relative levels of trade liberalisation. And it can be quite a big deal. As Lucian observes:

The role of processing trade has come to the fore in the context of the rapid integration of China in GVCs. The processing trade facilitation scheme, coupled with special economic zones and the facilities offered to foreign companies interested in assembling various manufactured products in China has been credited with a large role in the impressive export performance of China over the last decades. The success of processing trade was outstanding, at some point reaching over 50% of the total value of Chinese exports. Even though in recent years China has moved away from this heavy reliance on processing trade, it still accounts for a significant share of Chinese exports, representing almost a quarter (24%) of total Chinese exports in 2020 (GAC, 2021).

And he argues processing trade could be more useful still. At the moment, firms have to navigate a large number of largely independent unilateral schemes and approaches. But what if there was an effort to joint these up and improve, interoperability? That would be pretty neat, right?

While the current unilateral schemes have worked relatively well, a multilateral or plurilateral approach aimed at ensuring inter-operability of such individual processing trade schemes would take these trade facilitation measures to the next level. By saving tariffs and unnecessary testing and certification costs (which remains a very costly component of international trade), it would facilitate tens of billions of euros worth of intermediate trade flows along global supply chains. There is also an opportunity for many developing countries to implement processing trade schemes that could be made compatible with the schemes in major economies like the EU, US, or China.

Cool job alert.

Go and work with Henry in Singapore. You know you want to.

Long live the moratorium

There is a currently a moratorium between WTO members that prevents them from applying customs duties to cross-border electronic transmissions. But it needs to be renewed. And every time it needs to be renewed India (and South Africa) threatens not to renew it.

The argument in favour of taxing cross-border electronic transmissions usually goes something like this: now that the world is moving online, governments that usually relied on tariff revenue to bolster their tax coffers are losing out. Taxing electronic transmissions is the logical next step: whereas before you would have applied a tariff to the imported DVD, now you apply it to the Youtube data. Or something like that.

Anyhow, with thanks to Shantanu Singh for flagging, it appears that India might be having a change of heart:

Apparently its officials have noticed that the free cross-border flow of data is actually in India’s interest.

Anyway, let’s see.

You GATS to be kidding me

MFN fan favourite, Nigel Cory, published a piece recently asking whether France’s new SecNumCloud “sovereignty requirements” – which “disadvantage—and effectively preclude—foreign cloud firms from providing services to [French] government agencies as well as to 600-plus firms that operate “vital” and “essential” services” – breach the EU’s WTO national treatment, market access, and most favoured nation under GATS:

France’s application of SecNumCloud to public—and private—sector players raises significant issues in light of the commitments that France and the EU undertook under the GATS, most particularly market access, national treatment, and MFN treatment. The early evidence is in: since its first introduction in 2016, only four companies—all French—have been certified under SecNumCloud. In essence, in both form and substance, this replicates China’s use of similar restrictions for foreign cloud services firms (for digital protectionism and authoritarian purposes).

Now while I am with Nigel that there is quite obvious discrimination, I think this would be a pretty hard case to win. As he mentions in the piece, France could fall back on public policy exceptions, or also, at the more extreme ends, the national security exception to justify its discrimination.

Given the state of its dispute settlement function, it’s also not clear that the WTO is the best fora to bring this dispute.

Which brings me to an alternative. The chaos-merchant in me wonders … is this something that could be raised under the EU-UK Trade and Co-operation Agreement? The exceptions issue is still present … but, y’know, it could be fun.

As ever, if you enjoy reading MFN, do consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Best,

Sam