There’s a scene in Succession, giffed above, where Logan Roy tells his scheming children that he loves them, but they “are not serious people”.

This is the last thing he ever says to them.

Anyway, I mention this because it’s how I feel nearly every time I see legacy Brexit commentary such as this. (Minus the “I love you bit”, because that would be weird.)

Because, c’mon. Chaps. Get a grip.

Or to put it another way, in what other context would “responding to the concerns of businesses and working to remove trade friction with your largest trading partner” elicit such a response?

Anyhow, taking each point as it comes:

Is the new EU-UK deal (documents here, here and here) a “Betrayal” of the Brexit vote?

To answer this, we only need to check one thing: Has it led the UK to rejoin the EU? Answer: No. Then, no, it is not a “Betrayal of Brexit.”

Will the new youth mobility scheme be a “return of free movement”?

On this, I’m going to give folk saying this the benefit of the doubt and assume they have never used a search engine to search for “youth mobility scheme” rather than being completely disingenuous.

Freedom of movement grants EU citizens the right to live and work in the UK indefinitely without a visa.

Youth mobility schemes — which the UK currently has in one form or another with Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Korea, Andorra, Iceland, San Marino, Monaco, Uruguay, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and kinda India — allow a “young person” (usually under 30, sometimes under 35) to apply for a visa that allows them to work in the UK for two years (note: sometimes three). These visas are often limited to a fixed number of young people from a given country in a given year.

At this point, it’s probably worth mentioning that the previous UK government attempted to negotiate bilateral deals on youth mobility with individual member states. And it wasn’t viewed as free movement then …

So, yeah. Not the same thing. Obviously.

Will the new deal bind the UK back into EU rules and the ECJ?

You know what? Yes, a little. The SPS Agreement will bind the UK to follow relevant EU food safety regulations, albeit with the possibility of limited exemptions. So yes, this agreement will result in the UK continuing to follow EU food safety rules. (In the context of the energy bit of the deal, there is also a bit of rule binding).

But the kicker here is … the UK was kind of doing this anyway. With a couple of small exceptions where either the UK moved more quickly (e.g., gene editing) or more slowly (the EU introduced some things the UK didn’t), every time the UK was given the option to diverge from EU food safety rules … it didn’t.

For example, under Prime Minister Boris Johnson, the UK faced down requests from the US, Canada and Australia to change its EU-inherited food safety rules in the context of FTA negotiations. Just a few days ago, Starmer managed to get a “deal” out of US without budging on food safety.

The revealed preference of successive UK governments is that they don’t actually think diverging from EU food safety rules will be popular. So they keep not doing it.

Given that, it probably does make sense to formalise the convergence and benefit from the not insignificant removal of trade friction currently plaguing UK food exports to the EU.

And yes, there are trade-offs. Of course there are. But much of the commentary is silly.

For example, an often-raised point is that following EU food safety rules will make it impossible for the UK to do trade deals. Now, I’m not sure about you, but I’m pretty sure that since Brexit, the UK has agreed to new FTAs with Australia, New Zealand, India, and the US (well, kind of not really, but you know what I mean) and acceded to CPTPP. Switzerland, a country also bound to EU SPS rules, has free trade agreements with quite a few countries the EU doesn’t have FTAs with, such as China and Indonesia. Given the point above — that no UK government actually wants to move away from EU SPS rules — binding itself to the EU and therefore being able to blame the EU if Donald Trump asks again probably makes everyones life a little easier.

On the ECJ point, yes, the UK has signed up again to the provisions it already signed up to in the context of both the Withdrawal Agreement and the Northern Ireland/Protocol: an independent dispute resolution mechanism that must take into account the intepretation of the ECJ when adjudicating over an intepretation of EU law. So yes, like the post-Brexit governments before it, this UK government has agreed a role for the ECJ.

Not on the list above, but given it comes up a lot: FISH.

Yes, the new arrangement will see the UK extend EU access to UK fishing waters for 12 years. But fish has always been complicated. Half the industry (onshore, farmed) kind of got screwed by the SPS checks that the deal is going to fix, whereas the offshore chaps were never going to be satisfied no matter what.

So yeah, Brexit was quite bad for the fishing industry, but not really for the reasons often given.

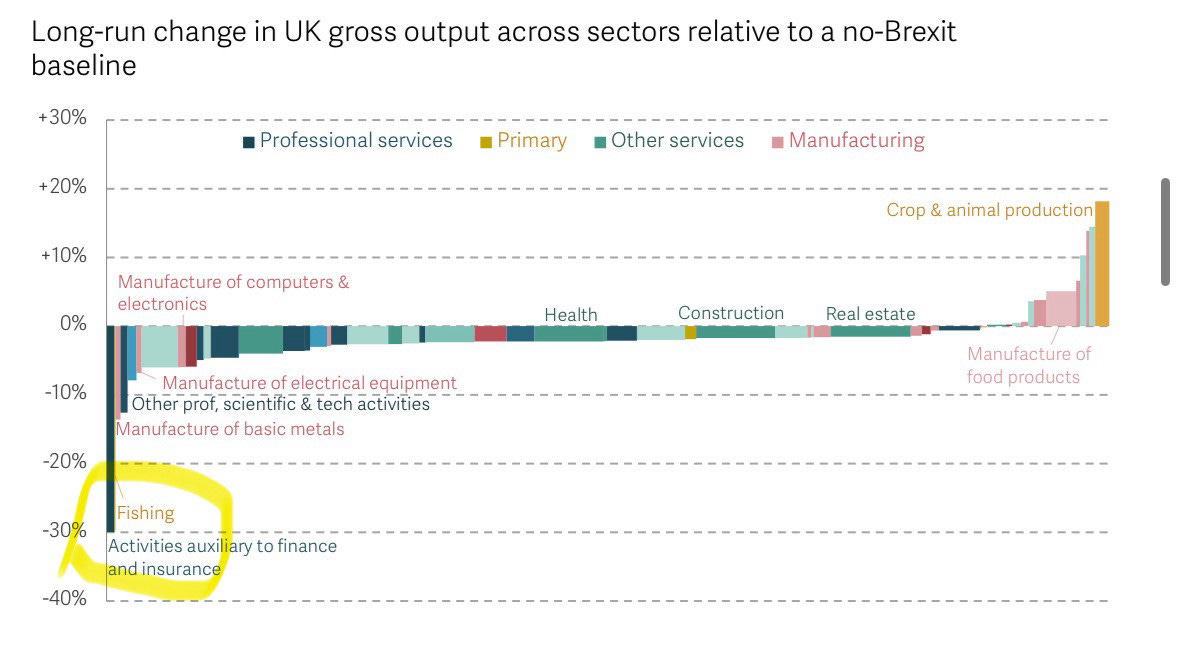

Chart via Labour MP Torsten Bell on Bluesky:

Anyway, my only real point here is that there is no longer any need to take unserious people seriously. Nine years after the Brexit vote, it’s surely time to start talking about what is and what is not in the UK’s trading interest sensibly again.

Best,

Sam

As someone in the relatively rare position of simultaneously being knowledgeable enough on trade to know what you mean by mutual recognition of conformity assessment bodies, and also being in favour of Brexit, I feel like I ought to give my thoughts here, as whilst I wouldn’t go as far as to call it a bEtRaYaL oF bReXiT, I do still think the deal obtained here really isn’t that great.

The key thing as you said, relates to fishing and SPS. Part of why I’m in favour of Brexit is that, having embarked on a project to essentially map what every country’s optimal economic specialisations should be, the UK is in an entirely unique position in the world in which it is both a large, developed economy, and has neither a substantial agriculture nor manufacturing sector within its specialisms. Whilst not every country is likely to want to push both manufacturing and agriculture, most countries care significantly about either one or the other, and so are likely to want to seek concessions in it with regards to trade, whilst also being highly protective of its own markets. This usually means trade negotiations are stalled to a tortured crawl with neither side really wanting to budge on anything more substantial than a few tariff reductions.

However, unlike essentially every other advanced country that isn’t Singapore, Ireland and a few others, the UK is almost entirely focused around services, and is arguably the best in the world at it. This puts it in an absolutely fantastic trading position, as it is simultaneously large enough for it to be worthwhile, is not likely to be a threat to your pet goods industries, is perfectly willing to open its own markets up to your industries, and the thing it’s asking for in return (services concessions) is either something you don’t care about or something which you’d actively benefit from closer links to London etc.

My concern is therefore that by tying ourselves to EU regulations, we are simultaneously removing our capacity to manoeuvre when it comes to making deals with others, and also doing so for the sake of an industry that frankly isn’t that important to the UK economy. Yes, it’s true that we’ve successfully signed trade deals with a tonne of agricultural focused countries, but this is largely a testament to other factors, and for most of them (fingers crossed India aside) they were generally lacking in services provisions - being able to turn around and say that we’ll let your food in without a bunch of stupid and unnecessary EU restrictions would be a viable additional concession to make in exchange for stuff we actually care about. Instead, we seem to be throwing this down the drain so Keir Starmer can use rule of three in his PMQs.

Furthermore, when it comes to agriculture, the one exception to our lack of specialty here is in fishing, and it is exactly this that we are arguably throwing under the bus for the sake of it. Ironically for a bloc which frames so many dubious regulations in the name of environmental standards , EU fishermen are notorious for annihilating marine ecosystems with their industrial trawlers - at this rate we will be giving up our viable agricultural sector and potentially forcing ourself to follow the rules (without a say) to destroy it. in favour of one which we don’t care about, and in a manner that harms our capacity to pursue future interests in areas we care about. At the very least charge them for the privilege like Norway does.

As for YMS, the big issue here is that the EU wants us to let their students use domestic fees, which as anyone who knows anything about university funding is a complete nonstarter. And beyond these areas, the only other thing we get is a bunch of commitments to “discuss” a bunch of areas which have been framed entirely in ways that heavily favour what the EU wants, including for some reason defence, which is entirely an EU benefit yet remains weirdly something they are trying to use as a bargaining chip?

If they were giving us something more substantial here (like say the aforementioned MRCAB issue, which is apparently okay for the US to have but not us), then I would potentially be more up for discussion. However as things stand, whereas I’m cautiously optimistic about the US and India deals, I simply fail to see how this remotely reflects the UK’s strategic priorities.

The text critiques the ongoing discourse surrounding Brexit, particularly the reactions to new EU-UK agreements. The author argues that many criticisms are exaggerated or misinformed, emphasizing that the new deal does not equate to a betrayal of Brexit, as it does not lead to the UK's rejoining the EU. The commentary highlights the differences between youth mobility schemes and free movement, and acknowledges that while the UK will continue to align with certain EU regulations, this was already happening. The author calls for a more rational discussion about the UK's trading interests, suggesting that it's time to move past sensationalist commentary and focus on practical implications. Overall, the piece advocates for a more serious and informed approach to Brexit-related discussions.