On 4 July the EU’s provisional tariffs on imported China-origin battery electric vehicles (BEVs) kicked in. I’ve written about these quite a lot, so I’m going to assume you know the basics.

Now that the tariffs have been in place for just over a month, we’re starting to get an idea of the initial impact.

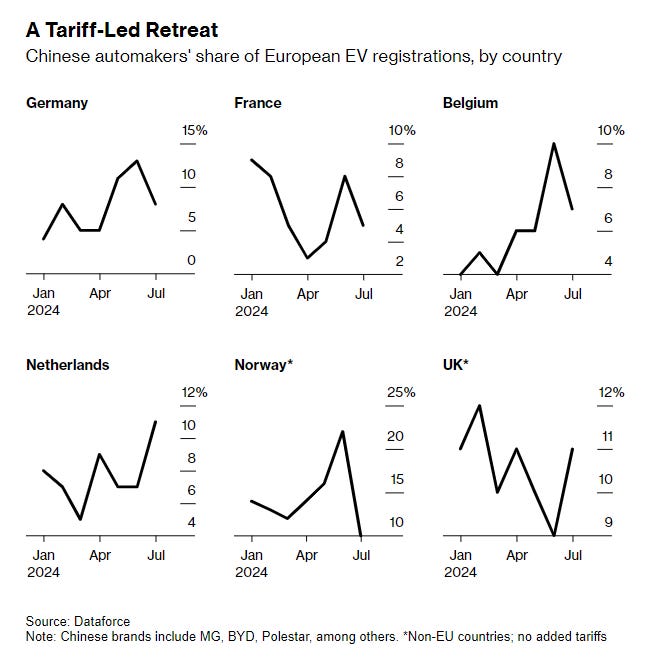

Bloomberg has produced these useful charts showing that, following a spike in the run-up to the tariffs in Germany, France and Belgium (something else is clearly going on in the Netherlands), there has been a drop off in China-brand car registrations in the last month or so:

In this context, the slight uptick in UK registrations is also interesting. See the same chart again but with arrows added by me:

This is because there is still a lot of uncertainty about whether the UK follows the EU (and US and Canada’s) lead in imposing its own tariffs.

There is definitely not enough evidence to take a solid view yet, but if the spike in imports/registrations continues, it opens up another possible route for UK tariffs, beyond the usual anti-subsidy or anti-dumping tariffs: safeguard tariffs.

Safeguard tariffs are different from anti-subsidy or anti-dumping tariffs.

Anti-subsidy tariffs require an investigation and proof that subsidies from a foreign government are allowing foreign exporters to compete unfairly in the UK market, and causing harm (or could cause harm) to UK industry. Anti-dumping tariffs require an investigation and proof that a foreign company is selling into the UK at unfairly low prices, and causing harm (or could cause harm) to UK industry.

Safeguard tariffs can be applied if there is a surge in imports of a given product (or risk of a surge) and proof this is, or could cause, harm to UK industry.

This means that a spike in imports of Chinese BEVs into the UK, or fear of a spike in imports, as a result of the EU imposing tariffs and diverting the cars elsewhere could be used to justify a safeguard tariff.

For context, the same logic was used by the EU to justify applying tariffs to imported steel following Trump’s imposition of steel and aluminium tariffs.

The wider appeal of safeguard tariffs is that they can be provisionally implemented very quickly, if needed. This means the UK wouldn’t have to wait 9 months or so for the provisional results of its own anti-subsidy/anti-dumping investigation.

But there are also some massive downsides to this approach.

Namely: safeguard tariffs are an absolute nightmare to administer.

When applying a safeguard tariff, instead of targeting the tariff against the country you are most concerned about, you have to apply it universally to all imports of the product (with some exceptions relating to developing countries).

This means that, in this instance, the UK would need to apply an additional safeguard tariff to all imported BEVs.

The UK could then choose to exempt certain countries from the tariff by creating an annual tariff-rate quota (TRQ), allowing for a fixed quantity (usually a volume based on historical flows) to enter at the normal tariff rate.

Working out what these TRQs should be on a country-by-country basis, and then administering the TRQs is haaaaaaaard work. You also run the not-inconsiderable risk of pissing off all of these countries too.

So while the UK is definitely thinking about safeguards, my guess is that it would prefer not to.

Bad data

The CFR’s Brad Setser has written a very good thread about why China’s trade data is complete garbage at the moment.

Read it here:

Forced Labour

My general trade theory of everything is that when the US and EU intervenes in a way that changes the global market dynamics, other countries tend to follow.

The logic is as follows: tariffs in Country A lead to more of the tariffed-product being diverted to Country B which leads to domestic pressure on the government in Country B to impose tariffs, etc.

You can see this, for example, with the EU CBAM which the UK is going to copy. Also the EV tariffs on Chinese BEVs where the US imposed tariffs so the EU imposed tariffs so Canada will impose tariffs and the UK … tbc.

Forced labour rules have the same dynamic, I think. The US has the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, and the EU will soon have its own Forced Labour Regulation which could mean that impacted products, such as solar cells, will be diverted onto other markets such as the UK.

Annnnnd … the pressure is building in the UK. As flagged in this morning’s Politico Morning Trade, a campaign group called the Anti Slavery International has published a report arguing that the UK should follow the EU’s lead.

They argue that:

The UK’s failure to keep pace with global efforts to address forced labour in value chains risks the UK becoming a dumping ground for goods tainted with forced labour.

Anyway, I think this one will run and run.

I’m actually on holiday this week. Here is a behind-the-scenes snapshot of the MFN writing process:

Best,

Sam