In January I wrote about the concept of a Sanctions Union, which is kinda like a customs union but specifically for sanctions.

To recap:

Generally speaking, if two (or more) countries are in a customs union it means that they have made a decision …

not to apply tariffs to goods moving within the customs union

to apply an equivalent tariff to imports from non-members.

The primary benefit of a customs union over a free trade agreement is that the tariff-free trade between its members is the default. This is different from a free trade agreement (FTA), where the tariff-free trade is conditional on the traded product fulfilling the FTA’s rules of origin requirements.

In an FTA scenario, the rules of origin requirements are necessary to determine whether the product originates in one of the FTA countries and, therefore, qualifies for tariff-free trade. Without rules of origin, goods made somewhere else in the world could benefit from the preferential treatment if they were transhipped via the territory of one of the FTA members.

For example, assume country A has a FTA with country B. But country A applies a 0% tariff to widgets from country C, while country B applies a 10% tariff to widgets from country C.

Without rules of origin, widget makers in country C could export to country A (0% tariff) and then tranship the widgets onward to country B, making use of the FTA between country A and avoiding the country B tariff on imports from country C

Within a customs union, this is not a problem. Both country A and country B would agree to apply a tariff at the same rate (say, 5%) to widgets imported from country C. The risk of circumvention is therefore removed, which removes the need for rules of origin requirements.

This is useful for businesses because rules of origin provisions are annoying, and compliance can be time-intensive and costly.

And then …

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU introduced sanctions on Russian iron and steel (and lots of other things). As of 2023, these sanctions not only bar the direct import of Russian iron and steel, but also steel products that have been processed in countries other than Russia that incorporate Russia-origin iron or steel inputs.

In practice, this means that EU importers of steel and iron products now need to demonstrate the origin of their goods, and present mill test certificates to prove that none of the steel and iron inputs originate in Russia.

These requirements have created some issues for, say, UK steel exporters to the EU, who need to comply with the new obligations despite the UK having the exact same sanctions in place on Russian steel and iron inputs (meaning the risk of any UK export to the EU incorporating sanctioned inputs is minimal).

The solution? A Sanctions Union, of course!

And the EU has already got going with this. In its December 2023 sanctions package, the EU included provisions adding Switzerland [Norway was already named] to its list of countries exempt from the obligations, given it applies the same sanctions directly.

At the time, the UK was conspicuously absent from the EU’s list.

But no more!

In its 13th sanctions package (released in February, but I only noticed this now), the EU decided to let the UK join its Sanctions Union:

Nice.

You EFTA Give It To ‘Em

As some of you will have seen, the EFTA countries (Norway, Iceland, Switzerland plus kinda Liechtenstein but as it is in a customs union with Switzerland it gets treated slightly differently) have concluded a trade deal with India.

The agreement is pretty useful to look at as an indicator of what India is happy to sign up to when not pushed particularly hard. For example, India has offered no tariff liberalisation on sensitive sectors such as automotive and whiskey (and, understandably given the countries involved, I can’t imagine any of the EFTA states care too much about this.)

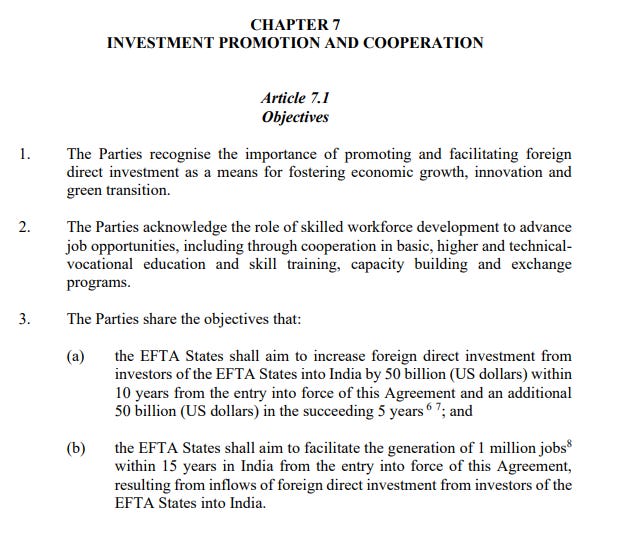

Most interesting are the provisions included to incentivise investment from the EFTA countries into India.

The agreement conditions Indian tariff liberalisation on EFTA states aiming to “increase foreign direct investment from investors of the EFTA States into India by 50 billion (US dollars) within 10 years … and an additional 50 billion (US dollars) in the succeeding 5 years” and them facilitating “the generation of 1 million jobs within 15 years in India”.

How is this going to work in practice, I hear you ask?

For that, I recommend reading Devon Whittle’s excellent post over at his Substack Trade Notes. Do read and subscribe:

CBAM

As of yesterday, you have until 13 June 2024 to submit your response to the UK’s new CBAM consultation.

As a recap, the UK is being begrudgingly forced to introduce a CBAM because the EU is doing one. However, the current UK government has decided it can’t really be bothered to do it, so has kicked the can until 2027 to ensure it is a problem for a future (probably Labour) government instead.

To kill the time, they are doing another consultation that a future government may or may not pay attention to. Alternatively, they may decide to do another consultation.

Best wishes,

Sam

Interesting as ever, Sam. Regarding the ‘Sanctions Union’, can you clarify what this means? Is it that the UK has in some way applied to be on the partner list and/or has tailored its own package of sanctions so as to make it eligible to be on the list? Or is it simply a unilateral EU decision and made on the basis that ‘as it happens’, UK sanctions are “substantially equivalent” to those of the EU? Conversely, does this apply the other way round i.e. does the UK recognize the equivalence of EU sanctions? Chris G