If you’re an exporter, there are worse things in the world than tariffs.1

A tariff is an additional cost when selling into a market. This can result in your product being less competitive (tariff cost passed onto the consumer), your company making less money (tariff cost absorbed via lower profit margins), your staff being annoyed (tariff cost passed onto the labour force via wage suppression), your suppliers being unhappy (tariff cost passed onto the supplier down the supply chain), or a combination of all of the above.

But the point is that a tariff doesn’t [neccesarily] prevent you from exporting your product.

So what’s worse?

Well, someone telling you that, for whatever reason, you are not allowed to sell your product into a certain market.

This could be because your product doesn’t comply with local regulations (for example, Canadian beef produced with hormones can’t be sold in the EU or UK), the product or company being sanctioned, or because the product being exported is subject to export controls.

In this instance, the impact is a lot more binary: yes/no.

Given this, it is worth considering which sectors might be most exposed to the new EU forced labour regulation, which went live yesterday (12 December 2024).

The regulation states that from 14 December 2027, “economic operators” will be prohibited from placing products made with forced labour on the EU market and from exporting them from the EU. Companies found to have breached the regulation may be required to remove the offending product from the EU market and potentially destroy it in a pillar of fire.

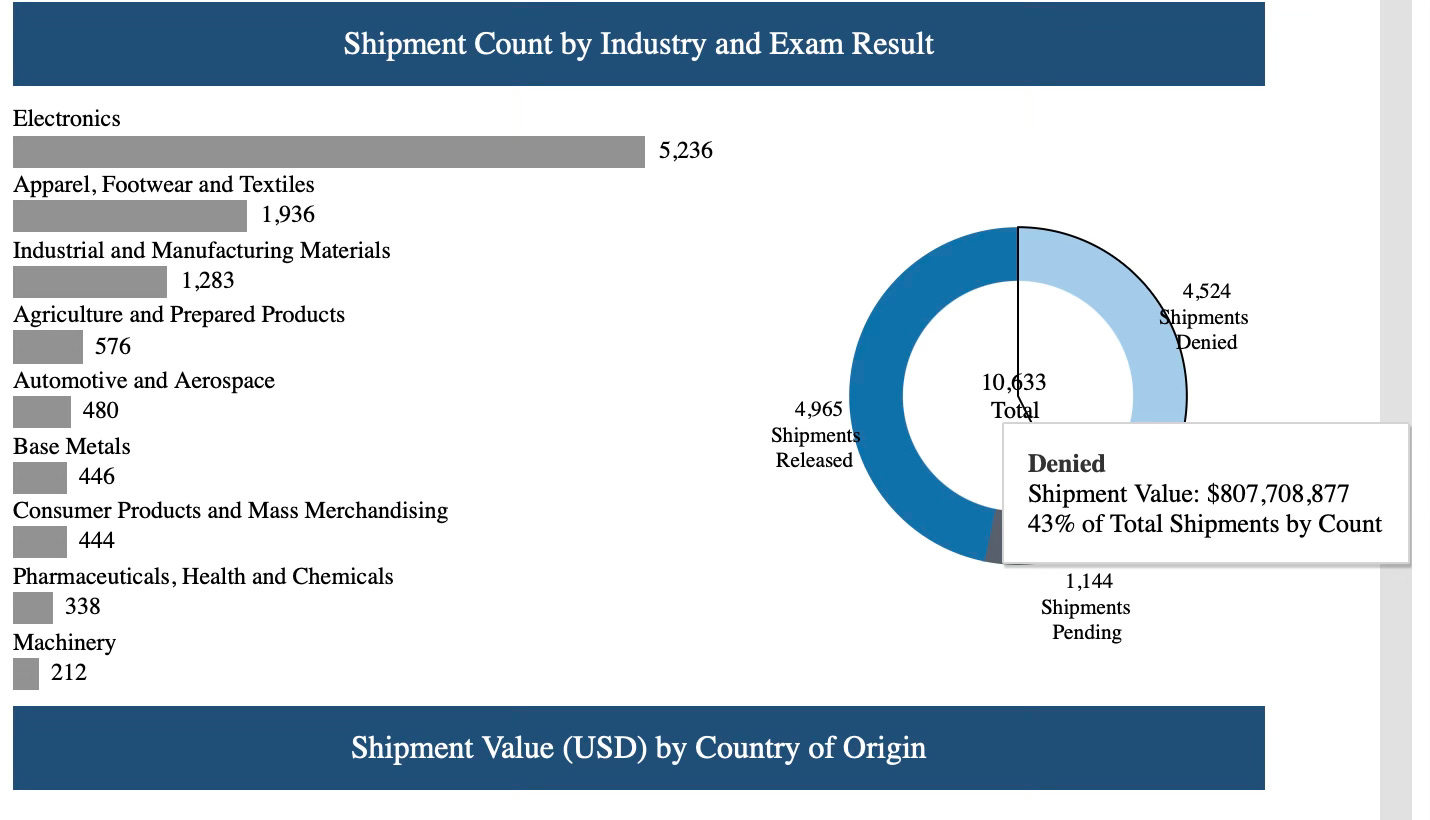

Given this regulation has some parallels with the US’s 2021 Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, we already have an initial view of which sectors are getting caught:

Within these broad categories, we also know there is significant scrutiny of electric vehicle batteries and solar.

One notable difference between the EU regulation and the US regulation is that the EU regulation is much broader. The US rules apply exclusively to products linked to forced labour in Xinjiang, while the EU rules apply to all products regardless of their country of origin.

This widens the possible product and geographic scope quite considerably.

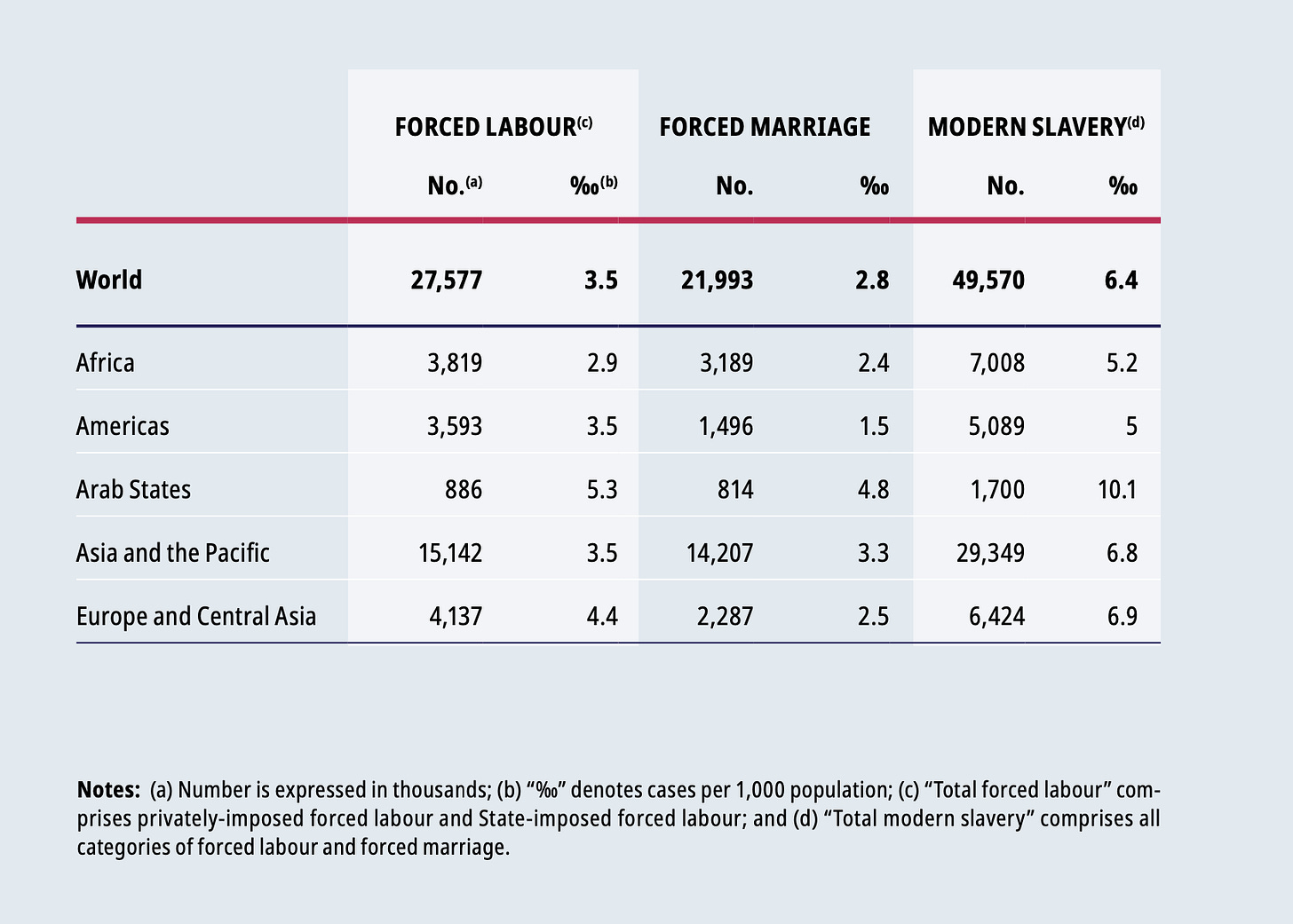

According to the ILO, forced labour occurs … pretty much everywhere:

However, there is another important difference between the EU and US approaches, which may soften the impact at the border.

In the US, products linked to Xinjiang are presumed to be linked to forced labour unless the importer can prove otherwise. Under the EU regulation, the burden of proof will be placed on “competent authorities” (see: whoever each member state tasks with enforcing the regulation or the Commission, depending on the context) who will need to provide evidence of links to forced labour before taking action.

In practice, I imagine compiling the evidence and completing an investigation will be fairly time and resource-intensive, limiting the regulation’s application.

However, ahead of entry into force, some EU sectors are already campaigning for the restriction of foreign products, so there may be a few high-profile scalps early on.

Update: A couple of readers have written in to say the better US/EU forced labour comparison is with the US’s Withhold Release Orders (WROs). WROs apply more broadly than the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act but the burden of proof is similar to the EU legislation. I think this is fair — I should have done this. But the point on burden of proof still holds — if people are expecting the EU forced labour regulation to have a similar impact to the US Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act (4,524 shipments denied!), I think they are wrong. But yes, the number of enforcement actions could certainly look similar to the WROs:

EU-Mercosur … completed it, mate

The EU has finally concluded its FTA negotiations with the Mercosur trade bloc (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay) … again.

I’m quite sceptical that this agreement with ever enter into force, but putting that aside for a moment, it is probably helpful to think about the impact of the deal if it does.

The first thing to say is that it is kinda a big deal, literally.

As a rule of thumb, a trade agreement will be economically significant if the country (or countries) you are negotiating with a) has lots of people and b) has high barriers to trade.

According to Google, just accounting for Brazil in Argentina, we are talking about a combined population of over 250 million people and applied tariffs are high.

So yeah, cool.

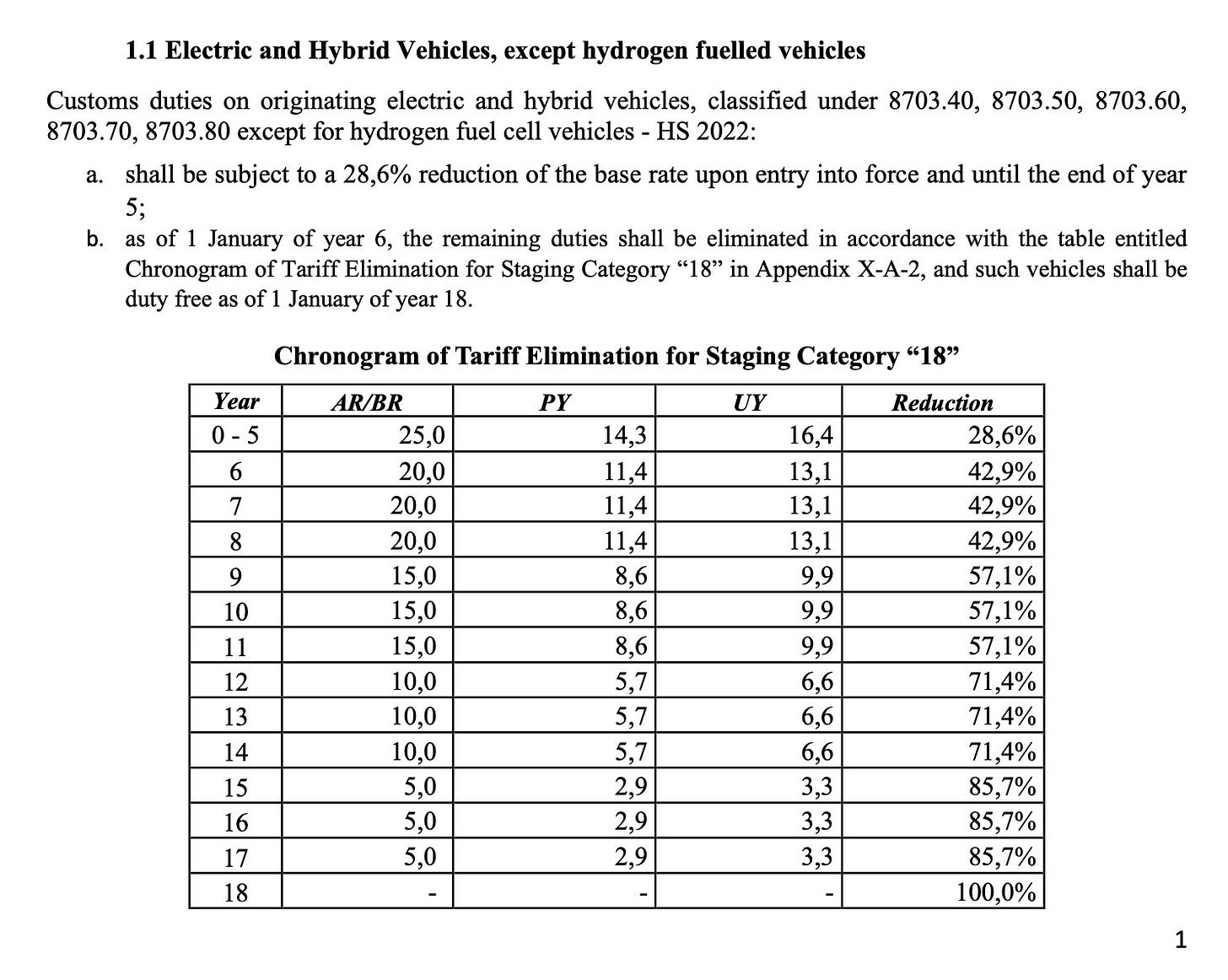

Although for EVs, for example, the tariff phase-out might take a little while:

It’s also worth thinking about whether the agreement could trigger other countries trying to get in on the game.

This is because an FTA such as this not only makes EU exports to Mercosur more competitive compared to domestic Mercosur producers but also more competitive than exports from, say, the US and UK.

So, who’s next?

Reciprocity

Former DG Trade negotiator Ignacio García Bercero and his new colleagues at Bruegel have written a new paper brainstorming the possible EU response to Trump tariffs.

It’s worth read the whole paper to get an idea of possible EU thinking, but this proposal jumped out [emphasis added]:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Most Favoured Nation to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.