On 17 and 18 September 2024, hundreds of pagers and walkie-talkies used by Hezbollah exploded as part of an operation reportedly orchestrated by Mossad.

On 23 September, the US Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) published a new proposed rule that “would prohibit the sale or import of connected vehicles integrating specific pieces of hardware and software, or those components sold separately, with a sufficient nexus to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) or Russia”.

The two events are of course not linked. But at a conceptual level, the details surrounding the former, where everyday communications equipment was successfully co-opted for military means, do help make sense of the latter.

Launching the new regulation, US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said:

“Today, the U.S. government is taking strong action to protect the American people, our critical infrastructure, and automotive supply chains from the national security risks associated with connected vehicles produced by countries of concern. While connected vehicles yield many benefits, the data security and cybersecurity risks posed by software and hardware components sourced from the PRC and other countries of concern are equally clear, and we will continue to take necessary steps to mitigate these risks and get out ahead of the problem”

And these new restrictions have been a long time coming.

As discussed in MFN back in July, the obvious next step for an America pulling every lever to keep Chinese EVs off its roads was to ramp up restrictions on connected vehicles.

Beyond generally keeping the American people safe from digitally hijacked cars, what does the proposed regulation actually do?

You can read it here, but in summary:

BIS is proposing regulations that would, absent a General or Specific Authorisation [emphasised the bit I think is particularly interesting],

prohibit Vehicle Connectivity System (VCS) Hardware Importers from knowingly importing into the United States certain hardware for VCS;

prohibit connected vehicle manufacturers from knowingly importing into the United States completed connected vehicles incorporating certain software that supports the function of VCS or Autonomous Driving System (VCS and ADS software are collectively referred to herein as “covered software,” as further defined below);

prohibit connected vehicle Manufacturers from knowingly Selling within the United States completed connected vehicles that incorporate covered software; and

prohibit connected vehicle manufacturers who are owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of the PRC or Russia from knowingly selling in the United States completed connected vehicles that incorporate VCS hardware or covered software. The prohibitions would apply when such VCS hardware or covered software is designed, developed, manufactured, or supplied by persons owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of the PRC or Russia.

Interestingly, the prohibition is narrower than it could have been.

In creating the restrictions, BIS also considered six systems it considered most at risk of being exploited by foreign adversaries:

vehicle operating systems (OS)

telematics systems

Advanced Driver-Assistance System (ADAS)

Automated Driving Systems (ADS)

satellite or cellular telecommunications systems

battery management systems (BMS)

But in the end, they argue a narrowly targeted rule focused on the systems that actually transmit data in and out of the vehicle on the basis that most of the other systems listed above rely on these to communicate:

BIS is proposing a rule that aims to strike a balance between minimizing supply chain disruptions and the need to address the national security risks posed by Connected Vehicles. BIS proposes to achieve this balance by focusing the rule only on those systems that most directly facilitate the transmission of data both into and from the vehicle, rather than focusing on all systems. Therefore, BIS is proposing to regulate transactions involving two systems of ICTS integral to connected vehicles, VCS and ADS. As further discussed below, in many cases, these systems serve as controllers for subordinate systems within the Connected Vehicle, like those highlighted in the ANPRM, making them a target for exploitation related to data exfiltration or remote vehicle manipulation.

The caveat here is that if any of the other systems listed above, e.g. the battery management system, have their own transmission capabilities then will be caught by the restrictions too:

BIS ultimately chose to exclude other systems highlighted in the ANPRM – such as OS, ADAS, or BMS – from this proposed rule unless they have VCS components and fall within the proposed rule’s definition of VCS hardware.

So, what’s the impact?

Pretty bloody massive!

Once in force1, any vehicle containing the prohibited hardware/software won’t be able to be sold in the US. This will impact not only Chinese brands, but also lots of other companies as well.

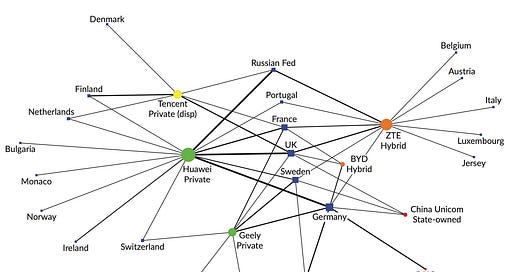

With a H/T to the ECFR’s Tobias Gehrke, this paper by Philipp Köncke and Nana de Graaff provides an illustrative example of the challenges faced by many firms with this graphic mapping out the geographical dispersion of Sino-European joint ventures across Europe:

And as with everything the US is doing of late, there is a non-unreasonable suspicion that this is not entirely about national security. Or to put it another way, it may be about national security, but in the run-up to a Presidential Election where being tough on China is a potential vote winner, publishing it now may have second-order benefits.

If you read between the lines, you can see that these restrictions double up as a useful tool for the US to prevent Chinese automakers from dodging China tariffs by setting up base in Mexico:

Chinese automakers, both state-owned and private firms, have leveraged their significant state-backed support, including subsidies, to fuel a global expansion that has seen Chinese automakers establishing foreign operations in countries like South Africa, the Netherlands, Thailand, Japan, and Brazil, among others, increasing the risks stemming from PRC auto manufacturing in third countries. This expansion, combined with recent investment announcements, has spurred concerns that Chinese automakers may soon seek to further expand into the United States either through exports or the establishment of additional manufacturing facilities. Some PRC-based companies have announced plans to establish manufacturing facilities in Mexico, which could enable them to receive favorable trade terms contained in the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Such a significant position within the global auto sector greatly expands the number of potential nexus points between PRC connected vehicle suppliers and U.S. automakers and U.S. consumers, including indirectly through auto manufacturers in third countries.

So what next?

These rules will be consulted on, probably tweaked a bit, and then brought into force over a number of years. But their impact will be felt before then, because why would you incorporate a China-linked VCS into the cars you are designing now if you know that car won’t ultimately be able to enter the US market?

I also assume that while the US is the first mover, this is an area where – like we saw happen with Chinese vendors and 5G infrastructure — we will see other countries follow.

The UK initiated its own review of the risks associated with connected vehicles earlier this year, and yesterday Politico reported that the EU is currently working on a “ICT supply-chain toolbox” that will cover connected vehicles.

Here we go again.

A quiz!

That was a bit intense, so to lighten the mood: a quiz. (Thanks to my Flint colleague Matteo Panizzardi for the idea.)

The EU has published the 42nd Report on the European Union’s (EU) trade defence activity.

In 2023, the EU initiated more than twice as many new cases as in 2022.

Without cheating, can you tell me which country has the most trade defence instruments in force against the EU?

Is it:

a) China; b) US; c) Russia; d) Turkey; e) Brazil; or f) Indonesia?

Answer on a postcard (email or comment below).

Between a rock and a hard place

CNBC reports that on 24 September China’s Ministry of Commerce opened an investigation into Calvin Klein’s parent company PVH, saying it:

“targeted Xinjiang suppliers in violation of the principles of normal market transactions, with disruptions to normal transactions with Chinese businesses, individuals and other people, along with other discriminatory measures.”

Translated, this is basically saying that by not sourcing from Xinjiang, a requirement for products sold on the US market, PVH is in breach of Chinese internal market rules preventing the company from discriminating against suppliers in Xinjiang.

My view is that we are going to see a lot more of this sort of thing, particularly when the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), and forced labour regulation come fully online.

Best,

Sam

BIS proposes to allow 1) until Model Year 2027, for connected vehicle manufacturers to come into compliance for transactions involving covered software, 2) until model year 2030, or January 1, 2029, for VCS hardware importers to come into compliance for transactions involving VCS hardware; and 3) until model year 2027 for connected vehicle manufacturers that are owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of the PRC or Russia to sell connected vehicles with VCS hardware and/or covered software. Moreover, to address concerns about the resources small businesses are able to devote to compliance, BIS is proposing a general authorization that would permit certain small businesses to engage in otherwise prohibited transactions.

Against the EU could be the US?

Here’s a link to the politico piece referenced (I couldn’t find it last night): https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-looks-to-follow-on-tackling-risk-of-chinese-car-software/