The Donald (Trump, not Tusk) has been talking about tariffs again. Specifically, he has proposed replacing income tax with tariff revenue.

This is of course nuts in the context of the US, where tariff revenue accounts for about 2 per cent of total tax revenue:

And as a general rule, tariffs aren’t (and shouldn’t be) a significant source of revenue for large developed economies.

But there is one notable exception to this: the EU.

And by the EU, I don’t mean the member states of the EU. I mean the actual central EU.

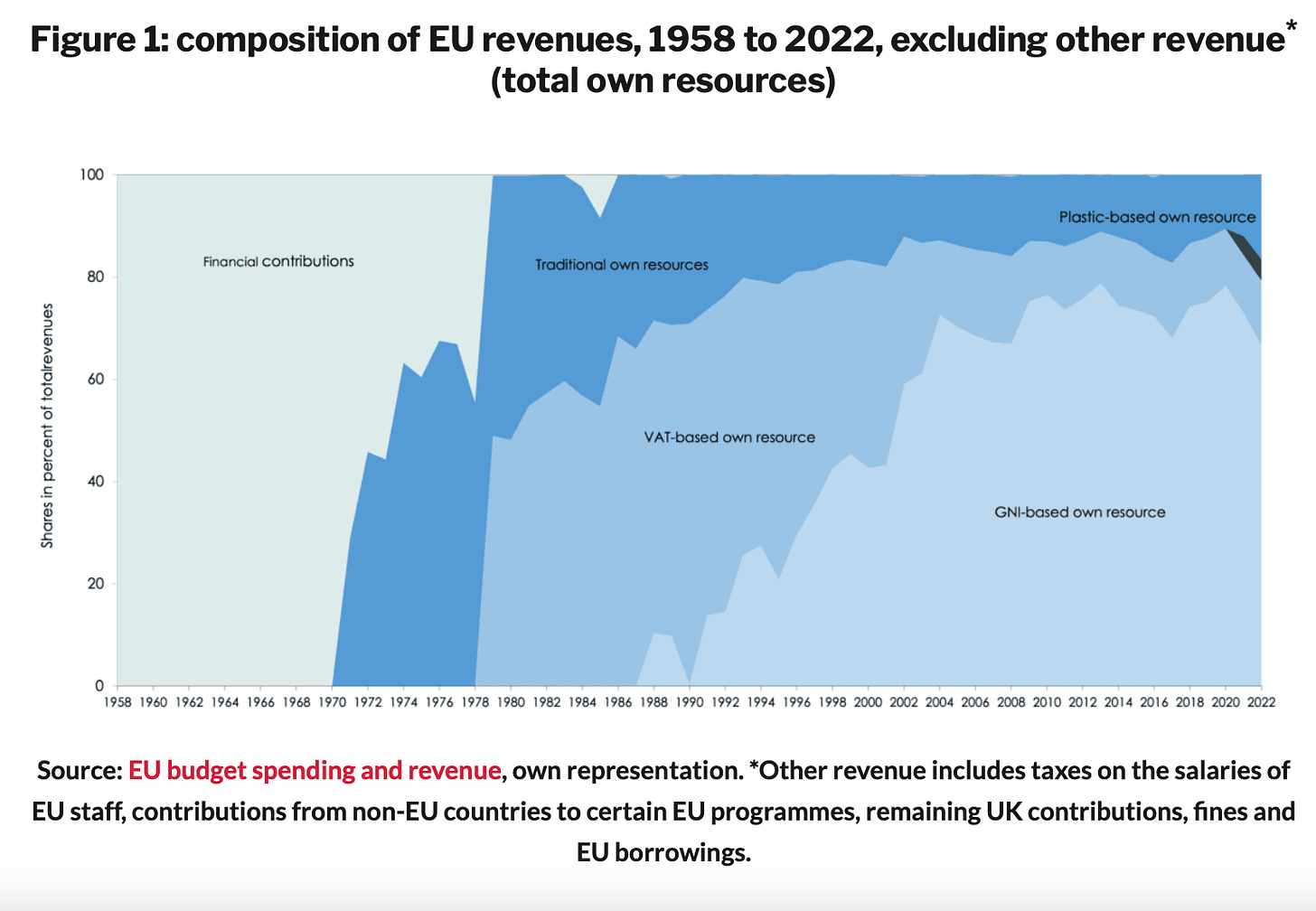

Despite falling considerably since the early 70s, customs duties (categorised in the Social Europe chart below as ‘Traditional own resources’) still account for just under 20 per cent of total revenue, around €18-20bn:

This means that, from a tax base perspective, the EU [central entity] is a bit more developing country than you might assume.

And while I do not think that DG Trade, in particular, thinks at all about revenue raising when applying new trade defence tariffs, or determining EU trade policy more generally … other parts of the Commission (DG TAXUD …) are upfront about their attempts to squeeze more customs revenue out of importers.

See its impact assessment justifying the new EU customs union reforms:

Which brings me to the point of today’s newsletter … how significant is the money raised by the EU’s new tariffs on imported Chinese electric vehicles?1

Before I get into this, a disclaimer: These figures are entirely back-of-the-envelope, incorporate assumptions made by me that may or may not be fair, and should not be treated as serious economic research.

With that out the way …

[If you just want the answer skip the bit below with bullet points]

In order to predict how much money the new electric vehicle countervailing duties will raise, first we need to make an assumption about the baseline import level of Chinese electric vehicles absent any tariffs, and then the impact of the tariffs on said import levels.

For the baseline, I’ve extrapolated forward the Rhodium Group’s finding that EU imports of EVs from China grew from $1.6 billion in 2020 to $11.5 billion in 2023, a year-on-year annual increase of $3.3 billion per year and assumed the EU would, absent tariffs, import $14.8bn in 2024 and $17.9bn in 2025.

Assessing the impact of tariffs requires me to make a judgement re: the impact of a tariff-induced price rise on the volumes of Chinese EVs imported. If, for example, a 10 per cent tariff resulted in a 20 per cent fall in imports this would mean an observed trade elasticity of 2.0. For the purpose of this exercise, I have used two assumptions, a higher trade elasticity of 2.156, drawn from this EU study, and a lower one of 0.8, that I have completely made up because I just don’t believe we’ll see a high elasticity in this instance.

Other assumptions: I’ve applied the 21% average tariff, rather than lots of different ones; I’ve used dollars for the import values and then an exchange rate of 0.8 to eventually convert to Euros for the purpose of calculating the tariff revenues; and I’ve assigned 75% of the eventual tariff revenues to the EU … because that is how it works (member states keep 25%). I’ve also assumed the existing 10% tariff is already baked into the current import volumes and tariff revenue.

Anyway, given all that, I reckon that the new tariffs will see 2025 imports between $3 (Low trade elasticity) and $8.1bn (High trade elasticity) lower than they would have been otherwise (Baseline).

In terms of tariff revenue, once you’ve applied a 21% tariff that equates to an additional €1.2bn-€1.9bn in the first full year of application (2025).

From an EU perspective, an additional €1.2-1.9bn isn’t huge, but is definitely nice to have! Particularly when you consider it needs to raise more money to start paying back some of the money it borrowed over the last few years.

To provide some context, this is possibly the same or higher than the estimated annual revenue of CBAM (€1.5bn), a key driver of new EU tax revenue, and higher than the estimated benefits of the aforementioned EU customs union reform (around €1bn per year).

So while making money was definitely not the reason these tariffs were applied, once they are fully in place, the fact they pull in a bit of much-needed cash might make it harder to scrap them in future.

Best wishes,

Sam

As a complete aside, I am currently in Italy and my father-in-law’s hire car was a very snazzy Chinese brand I had never heard of before. My daughter was a big fan (she liked the “cool lights”) and refused to travel in our car as a result (a Jeep, in case interested). However, a tyre on my father-in-law’s car burst on the way to the beach and the car has since been replaced by a Mercedes. A lesson? Probably not.