Most Favoured Nation: Contingent Liability

UK border checks, unintended consequences and de minimis thresholds

Welcome to the 102nd edition of Most Favoured Nation. This week’s edition is free for all to read. If you enjoy reading Most Favoured Nation, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

[Programme notes: Apologies for the late arrival of MFN. I spent the second half of last week in and out of bed, sporadically telling my wife I thought I might be dying. Turns out my body just didn’t like the new antihistamine I was trying. So there we go. Not dying. All fine.]

Let’s say I am one of those high-trust people who constantly leave their front door unlocked. I might go through my entire life without an issue. Alternatively, the first time I leave the door unlocked, a local criminal could walk in and walk off with my TV.

This is a contingent liability — defined as a liability that may occur depending on the outcome of an uncertain future event. But one I could quite easily plan for.

For example, I could tot up the rough value of the things in my house and put that money into a savings account. If someone walks in and robs me, I’ve got it covered, but in the meantime, I get to keep the warm glow of … I dunno, being a high-trust person who doesn’t believe in locking their door.

But what if the potential liability is unquantifiably massive?

This is the sort of thing governments have to wrestle with all the time. To use a still-slightly-topical example: pandemics.

Governments everywhere have “global pandemic” near the top of their risk register. So how much money should they spend planning for a global pandemic that may never happen? How much PPE should they in warehouses? How many hospital beds should they hold in reserve? How much excess capacity should they build into their health systems?

Bear in mind this is all money that could be spent on things that are more immediately pressing and definitely happening. And, of course, the longer something doesn’t happen, the more difficult it is to justify spending money “just in case”, even if the reason it hasn’t happened is just that you have just been phenomenally lucky.

Anyhow, the concept of contingent liability is important when thinking about the UK government’s approach to post-Brexit border management.

In the immediate aftermath of the UK exit, the government decided not to impose regulatory controls on agrifood products entering the UK directly from the EU. This is despite the fact that deciding not to do so created an asymmetry with the EU, which applied its normal third-country agrifood inspection regime to UK imports from pretty much day one, and a discrepancy vis-a-vis how the UK treated agrifood imports from the rest of the world.

The UK's decision to do this was probably sensible [I am pretty sure you could find me saying as much in the press at the time if you can be bothered to search through Google].

Why?

Well, to give a few reasons: the UK didn’t have the infrastructure to carry out these checks, nor the personnel; imposing checks on food from day one would have ground the border to a halt; there was no need to, given the UK and EU food health regimes were directly equivalent immediately after exit; the EU and its member-states are a trusted regulator, so there probably wasn’t very much to worry about; it would add to the tangible costs of leaving the EU and make Brexit and politicians implementing it look bad.

Over the next couple of years, the UK then repeatedly threatened to impose these checks before repeatedly kicking the deadline further into the future. But now, with a new deadline of 31 October 2023, perhaps this time, the government will finally do it?

The draft Target Operating Model [which will be tweaked before implementation] says:

We propose to implement the model through three major milestones:

31 October 2023 - The introduction of health certification on imports of medium risk animal products, plants, plant products and high risk food and feed of non-animal origin from the EU.

31 January 2024 - The introduction of documentary and risk-based identity

and physical checks on medium risk animal products, plants, plant products and high risk food and feed of non-animal origin from the EU. At this point, imports of Sanitary and Phytosanitary goods from the rest of the world will begin to benefit from the Target Operating Model. Existing inspections of high-risk plants/plant products from the EU will move from destination to BCPs.

31 October 2024 - Safety and Security declarations for EU imports will come into force from 31 October 2024. Alongside this, we will introduce a reduced dataset for imports and use of the UK Single Trade Window will remove duplication where possible across different pre-arrival datasets – such as Safety and Security, Sanitary and Phytosanitary, and pre-lodged customs declarations.

BUT WILL IT ACTUALLY HAPPEN?

I should caveat by saying that I have pretty much made a post-Brexit career, at least on the implementation side of thing, by saying “nah, they’ll kick the can again” in response to every UK self-imposed arbitrary deadline.

But maybe this time is different.

Why? It comes back to this notion of contingent liability.

As it stands, the UK has loads of food entering via the EU that isn’t being checked and who knows what state it is in. 99% is probably fine, but 1% could very easily contain the disease, ultimately kill someone, wipe out UK crops, introduce disease and pestilence, etc.

And how much would that cost? Financially, potentially a lot of money. Politically? Also pretty severe.

And while politicians have, until now, been willing to kick the can and cross their fingers, the UK political context has changed a bit.

By that I mean, the UK is currently running an inquiry into the UK’s Covid-19 response where a lot of decision-makers are going to come out looking incredibly bad. This context means that the current group in charge are a bit more cautious about putting their name to a further extension of a policy — no checks on potentially risky imports — that could, in a worst-case scenario, have some pretty bad outcomes.

Or to put it another way, people have become a little more reluctant to be named as the person responsible in the “imported avian flu wipes out all of the Queen’s swans scandal” or similar in the inevitable subsequent inquiry.

So, to nail my colours to the mast, while there are still good reasons to think the border controls will be can kicked again — for example, high food inflation and a lack of political benefit to making the border more unmanageable for some importers in the short-run — I think some form of controls will be introduced at the end of October, at least on paper. I then don’t think they will be properly enforced due to some of the structural issues — lack of infrastructure and personnel, for example — being as true now as it was back then. But at least if something goes wrong, the government can say it tried.

Unintended consequences

One of the fun things about trade policy, and indeed most policy, is unintended consequences. Whatever the intervention is, something no one (or not many people, at least) thought about will happen.

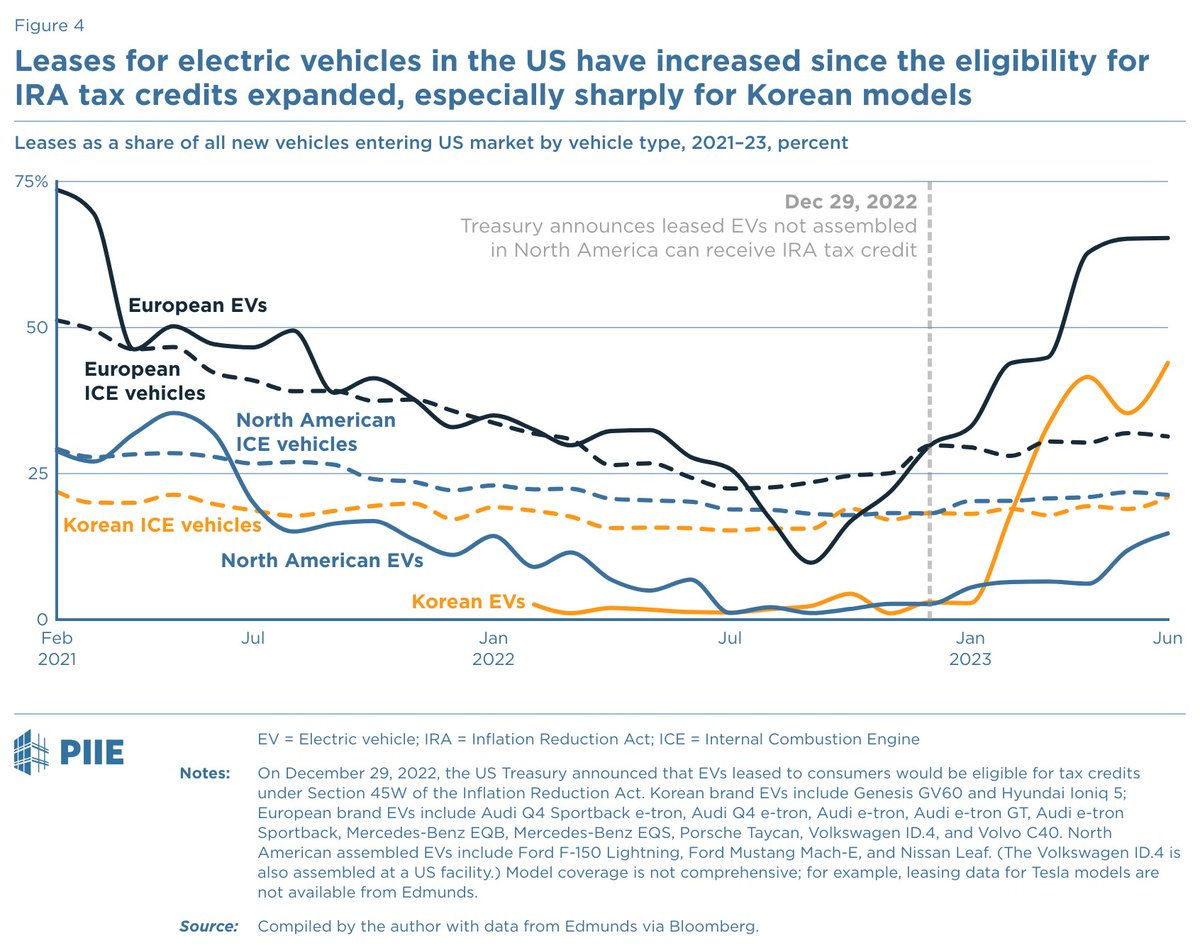

So that is why I love this Chad Bown chart. On December 29 the US Treasury released some guidance saying that leased vehicles assembled outside of the US are eligible for the Inflation Reduction Act’s EV tax credits.

Then this happened:

lol.

Read the full Chad report here.

De minimis threshold

I’m pretty sure I have written about this before — because it’s a topic I love — but in case not:

Most countries don’t apply tariffs to goods valued below a defined threshold. This is known as a duty de minimis threshold. And where countries set this threshold tells you quite a lot about both their risk tolerance and their inclination towards trade liberalisation, or not. For example, the EU’s duty de minimis threshold is €150 (the UK’s is £135) while the US’s is a massive $800!

See:

In practice, this means that loads of consignments imported into the US are not subject to tariffs, even if duties would normally apply. This is good for consumers, and it also reduces the burden on companies and customs officials, who don’t need to worry so much about enforcement and the cost of collection (which can be greater than the value of revenue raised).

But de minimis thresholds are not without risk. Particularly in systems which remove tariff obligations **and** provide for reduced administrative burdens, a de minimis threshold can lead to lots of crime. And by crime, I mean fraud, in the form of deliberate customs undervaluation, with packages deliberately mislabeled to keep them below the threshold.

With thanks to customs guru Anna Jerzewska for flagging, the EU is considering removing the de minimis threshold as part of its customs reform.

As above, there are some understandable reasons for this … but it’s also a bad idea. A new study from Copenhagen Economics says:

The removal of de minimis thresholds on duties would have a significant impact on time to trade and customs administration and economic operators’ increased complexity and costs that are hardly offset by revenue collection. Ultimately, this additional complexity and associated costs would fall onto businesses and consumers who might suffer significant welfare losses due to higher prices, less choices, and less efficient markets.

So yeah, not good.

Best wishes,

Sam

Another result of crying wolf and then kicking the can down the road is additional cost for traders. They have to plan and invest for whatever the latest deadline is going to be and will often ship more product in advance of the deadline to avoid disruption. A nightmare for them and for trade statisticians!

Thank you. Wishing you a quick recovery. Investment in earthquake prevention measures is a similar problem to pandemics. Politically it is difficult to get rewarded by voters, but after the earthquake it is a golden opportunity to show off / capitalise on the disaster and promise everything.