Most Favoured Nation: PEM to the Rescue?

A freeport in the cabinet office, EV rules of origin, digital trade and the cost of isolation

Welcome to the 95th edition of Most Favoured Nation. This week’s edition is free for all to read. If you enjoy reading Most Favoured Nation, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

(As an apology for missing last week due to a hospital appointment – this week’s edition is absolutely mega.)

I am not one for spreading unsubstantiated rumours. That is unless the rumours are so good, and I am so desperate for them to be true, that it would be rude not to. On that basis, I recently heard an incredible rumour that goes something like this:

Back when Theresa May was Prime Minister, a foreign government gifted her an expensive sword. Unfortunately, this sword is made of ivory, which is controversial because people like elephants/rhinos/narwhals. So, to avoid having to declare this and avoid offending the gifting country by giving it back, the UK government decided to create a quasi-freeport (or diplomatic suitcase or something) within the cabinet office, where the sword lives in territorial limbo – like Tom Hanks in the Terminal – to this day.

Now let’s be honest, there is only like a one per cent chance this is actually true. But if it is true, I would be so happy.

---

PEM

I know you are all sick of talking about battery rules of origin. But to re-cap: the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) includes specific rules of origin provisions for electric vehicles (EVs), EV batteries, and EV battery parts designed to gradually force EU/UK car producers to source their batteries locally.

At the moment, EVs and their batteries can qualify for tariff-free trade under the TCA fairly easily, even if their batteries are sourced from outside of Europe. From 2024, the rules of origin tighten, and it will become more difficult to do this. And from 2027, the battery must be sourced in the EU/UK for an EV traded between the two partners will not qualify for the TCA.

As I have written many times before, this poses a bit of a problem. Because while European battery-making capacity has increased over the last few years, it has not increased sufficiently to meet the demands of the EV industry. To be more specific, we still do not create enough active cathode material (the chemicals used to create battery cells) in the EU or UK for carmakers to be able to comply with the new 2024 rules of origin when they come into effect.

Carmakers want to defer the 2024 deadline by a year or two to allow for domestic battery supply to catch up with demand. If there is no extension, then EVs traded between the UK and EU will be hit with a 10% tariff, while combustion engine cars will continue to trade tariff-free.

Anyhow, this discussion has started to gain a bit more attention of late, with the UK keen for the deadline to be extended and the EU a bit more reluctant.

This week, as reported by the Financial Times, “two EU officials” have floated an alternative: why doesn’t the UK join PEM? [see: “Brussels urges UK to join trade pact to ease risk of post-Brexit car tariffs”]

I know what you’re thinking. What the hell is PEM?

For those of you who have been reading things I write for a **really** long time, you might remember I wrote an explainer on this back in 2017:

Originating *ahem* in 1997, the pan-Euro-Mediterranean cumulation system of origin fully materialised in 2005.

There are currently 23 Contracting Parties to the PEM Convention:

the EU,

the EFTA States (Switzerland, Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein),

the Faroe Islands,

the participants in the Barcelona Process (Algeria, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Syria, Tunisia and Turkey),

the participants in the EU’s Stabilisation and Association Process (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and Kosovo),

the Republic of Moldova.

All of the signatories to the PEM convention have agreed to replace protocols of rules of origin in the FTAs between each other with the rules of origin laid down in the PEM Convention, streamlining procedures across the zone.

The reason this could be relevant to the EV battery rules of origin discussion:

As to benefits: the PEM Convention allows for diagonal cumulation between all signatories to the agreement (so long as there are free trade agreement in place between all the Contracting Parties concerned). This facilitates the dispersion of supply chains across the zone, making it easier for exported goods to qualify for preferential free trade agreements between the various parties. (It also allows for full cumulation between some countries.)

But there’s a problem.

While PEM could help the auto industry comply with TCA rules of origin in general (given it would allow for diagonal cumulation with Turkey, Norway and Switzerland), and EV rules of origin in the longer-term, it would not actually help resolve the immediate problem.

This is because PEM allows for cumulation within the PEM (see: European) region … but the EV batteries are currently being sourced from China, Japan and South Korea. None of these countries are PEM members. [Note: one country PEM really would help is Norway — if the UK joins PEM Norwegian batteries would become qualifying for the purpose of EVs traded between the UK and EU.]

So the TL;DR: PEM could be useful, but it’s not a solution to the 2024 cliff edge.

There are also some further complications re: PEM. In that, it would only be useful if, and only if, the PEM rules of origin can run in parallel with the existing TCA rules of origin. This would allow EU and UK exporters to choose which rules to comply with when claiming the tariff preferences of the TCA.

(While this might sound odd, it actually happens quite a lot. For example, UK exporters to Australia will soon have the choice of either complying with the rules of origin in the UK-Australia bilateral FTA, or the rules of origin in CPTPP)

This is because the PEM rules of origin are not necessarily appropriate for the EU-UK relationship in all instances. There are no electric vehicle-specific rules of origin in PEM, for example.

But it is not immediately apparent to me that such a model is readily available. Running both sets of rules of origin in parallel would, at least, require some legal shenanigans. At this point, at least for now, it is probably easier to just extend the TCA’s 2024 EV deadline for another year or so …

---

Chart(s) of the week

The OECD’s new paper “OF BYTES AND TRADE: QUANTIFYING THE IMPACT OF DIGITALISATION ON TRADE” has some charts demonstrating that digital trade has been growing faster than non-digital trade:

- - -

Digital noodles

On the subject of digital trade, Stephanie Honey, who has been writing wonderfully about digital trade since before it was cool, has published a new paper looking at the proliferation of new digital trade chapters/provisions/agreements, with a focus on CPTPP, RCEP and USMCA, and raises concern that we may have “too much of a good thing”:

“While the scope and ambition are welcome, the proliferation of these new agreements in the Asia-Pacific and beyond (as Figure 1 illustrates) risks exacerbating fragmentation. Many of these new initiatives are bilateral, or among a ‘closed shop’ of a small group of countries. While such agreements will undoubtedly contribute to more seamless digital trade, they do little to tackle broader digital regulatory heterogeneity.”

I’ve been thinking about this, and I might have a slightly different view from Stephanie in this instance. First, I completely agree that regulatory fragmentation is a threat to digital trade and the global economy. If the EU and US go completely different ways on AI, for example, then there will be a big problem.

What I am not so sure about is whether the proliferation of different governance models in the content of FTAs matters so much. The noodle bowl concept is drawn from a problem we encounter in goods trade, where a proliferation of different FTAs and groupings results in different rules of origin and approaches and creates significant confusion for business and potentially trade diversion.

But I’m not sure digital provisions have quite the same impact. Whereas, for example, an individual bilateral FTA might have specific rules of origin which require a company to make deliberate sourcing decisions to qualify for tariff-free trade (e.g. Canada as part of USMCA) and these rules could come into conflict with a different FTA the same country has with a different partner (e.g. Canada in CETA), that’s not quite the case for digital trade provisions.

Very crudely, digital trade chapters tend to include the following commitments, with differing levels of caveats, detail and enforceability:

1. Both parties commit not to apply customs duties to cross-border data flows

2. Both parties commit not to force companies to store data on locally hosted computer servers, unless there’s a really good reason to do so. (Perhaps repeat this with some financial services-specific commitments)

3. Both parties will try to digitise their trade documentation

4. Both parties commit not to force companies to hand over propriety source code/algorithms as a condition of market entry

5. Both parties will recognise e-signatures

6. Etc.

And I’m not sure it matters if a country signs up to slightly different iterations of these commitments in a number of different deals, for example as the UK has done in the TCA with the EU, the CPTPP and then the DEA with Singapore. And the reason I say that is that I’m not sure how practical it is for countries to apply these disciplines differentially.

For example, it is hard enough to work out how to actually apply customs duties to all cross-border data flows entering a country … I have no idea how you would apply them to data flows ultimately originating from only one territory. So to my mind, it doesn’t really matter how many iterations of these commitments you sign up to, because in practice, you will always end up being held to the most stringent. De facto MFN treatment, if you will. In which case, every new iteration and improvement trickles down into a country’s commitments with everyone else. Which is good!

---

The cost of isolation

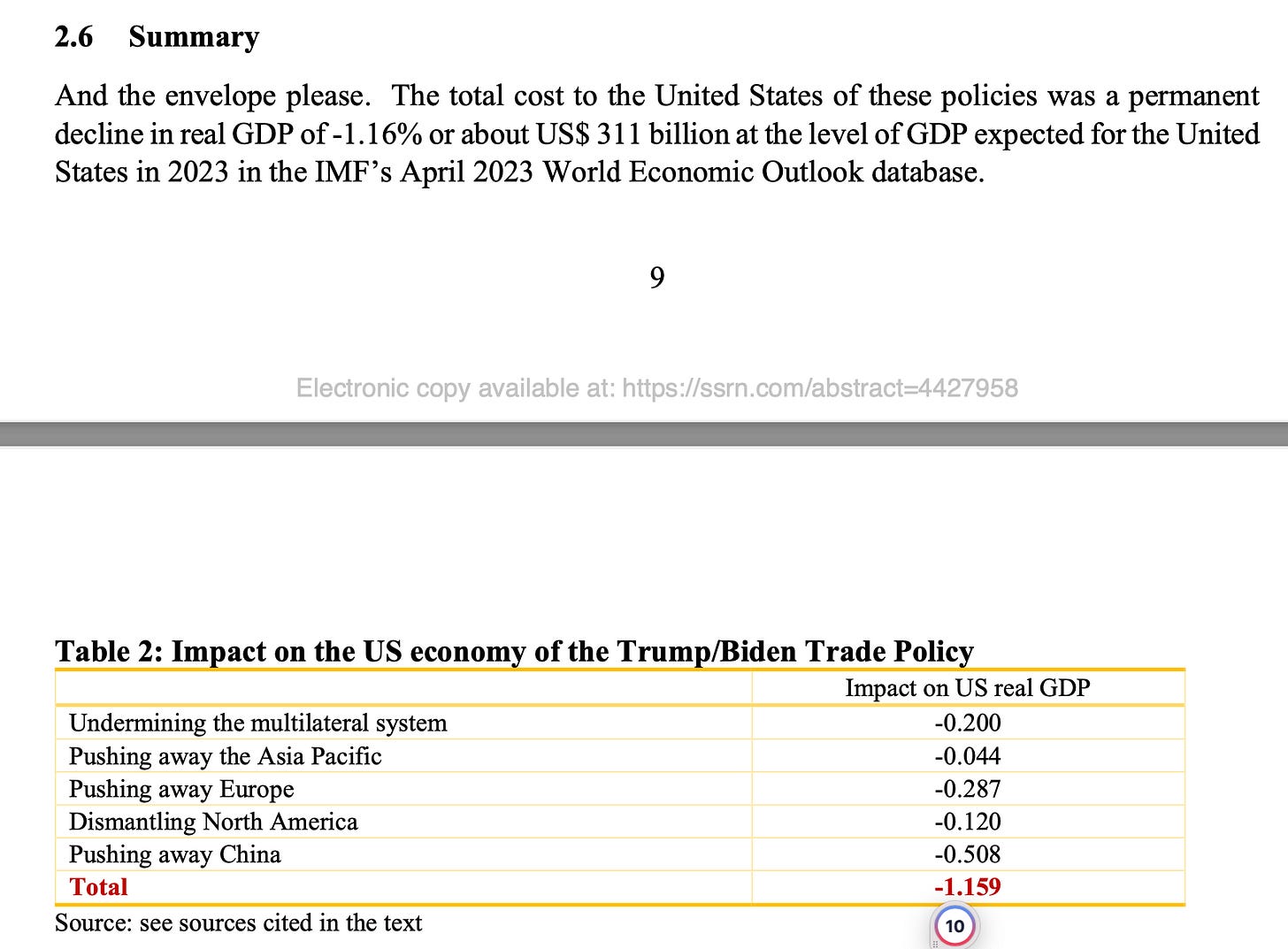

Have you ever wondered what the economic impact of American protectionism has been on the US? Well, Dan Ciuriak has attempted to model it. And, well, in the context of the US economy … it is significant, but not massive:

I’ve written before that the US is annoyingly not that reliant on international trade. Which is problem, given how reliant everyone else is on international trade with the US.

---

Best wishes,

Sam