Most Favoured Nation: Restoring Balance (Or Maybe Not) To Discussions Of Imbalances

Guest post by Karthik Sankaran

This is the third post by Karthik Sankaran, who has agreed to occasionally write for MFN on big macro issues that impact international trade and the global economy. Karthik has, at various times, been a modern historian, emerging markets journalist, and global macro portfolio manager and strategist. He is also an incorrigible and prolific source of terrible puns.

If you like what you read, please do sign up to Karthik’s Substack, which he promises to populate with more content soon. Meanwhile, he can also be found procrastinating on Twitter as @RajaKorman.

There are places that have supply and places that have demand; places that are capital constrained and places that have capital to go; places that are at the technological frontier, and places that are trying to reach or surpass it.

Well, we have yet another public fracas on globalization. It sort of began with a recent op-ed in the FT by Rana Foroohar arguing that “our understanding of comparative advantage is confused and damaging,” in turn inspired by a piece entitled "Can trade intervention lead to freer trade" by Michael Pettis. This then led to a rejoinder by Richard Baldwin, and counter-rejoinders by Gerard diPippo and Brad Setser on the rising recent contribution of net exports to Chinese GDP.

Meanwhile, I snuck in a snarky reminder about France’s key role as a financialized provider of double deficits and Euro-denominated safe assets to those insisting (for basically Whiggish reasons, I think) that the privilege/burden falls almost exclusively on the Anglosphere, and so on.

With this cast of characters, you might (rightly) surmise that said fracas involves a full-throated attack on globalization grounded in complaints about trade imbalances and their origins in persistent demand suppression in surplus countries; exhortations that a (highly improbable) coalition of deficit countries rewrite the rules of global trade; and then some actual numbers.

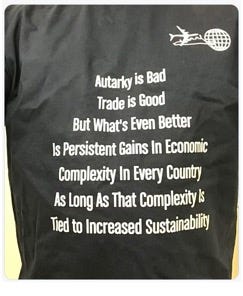

As to where I stand, I am a self-identifying “unhinged pro-globalization polemicist” so I’m obviously against Foroohar and Pettis on the big picture. Still, I have to acknowledge that Setser and diPippo are right (contra Baldwin) that the contribution of net exports to Chinese growth, having fallen in the mid-2010s, is now rising in a process that will probably continue for a while. So all that leaves me to contribute is my customary value-added (if any at all) to such debates: a combination of whataboutery and “actually, it depends” arguments regarding the seemingly dominant narrative.

Pettis’s original essay spends some time focusing on the falling manufacturing share of GDP in deficit countries — something I find problematic from an economic point of view, but useful because it conforms with my view of what actually motivates many anti-globalization complaints. I believe that for a great many people (primarily in the US, but increasingly in the EU), a stated concern about the size of global trade imbalances as a problem for the world at large conceals narrower domestic preoccupations with the sectoral composition of such imbalances and the associated consequences for domestic politics and the international balance of power. This might strike you as an entirely justified position for such people to take, or a cynical “d’uh!” observation, but I think it a point still worth making.

In this respect, I think Richard Baldwin’s critical intervention is not so much his recent view on the export contribution to Chinese GDP, but rather his 2016 diagnosis of the consequences of globalized supply chains engaged in unit-labor-cost arbitrage, buttressed by a combination in some countries of infrastructure, logistics, and those aspects of governance most important to capital.

This central feature of Globalization 2.0 led to a diffusion of technological and managerial knowledge, allowing countries with low levels of per capita income (even if measured at PPP) to produce complex goods comparable to those produced in developed markets at lower prices. I have waxed rhapsodic about this process at length here and within 280 characters here.

I also think, contra Foroohar and Pettis, that to argue that this process is the result of a damaging misunderstanding of comparative advantage (the example given is wine for cloth in Ricardo’s terms) is another kind of misunderstanding. Their misunderstanding consists of seeing patterns of comparative advantage as static and grounded in natural resource endowments, rather than dynamic and susceptible to change through public and private action and innovation. And continuing with the cynical observations, I have a sense that the nostalgia in the North Atlantic basin for the golden age from 1945-73 has an undercurrent of “things were good when poor countries not only stuck to doing poor country things like growing stuff or digging it out of the ground … they even charged us poor country prices when they sold it to us!”

I also think the balance of payments argument is a bit of a red-herring. This process of technological convergence through Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) driven by Unit Labor Cost (ULC)-arbitrage is likely to seem distasteful to many of those complaining that we are “misunderstanding comparative advantage” regardless of whether the recipient runs a trade deficit or a surplus. While there might be geopolitical reasons (friend/innocuous bystander/enemy-of-my-enemy variants of shoring) for politicians, think-tankers and other denizens of op-edistan to welcome more FDI flowing to Mexico or India, I would be very surprised if the actual (or even stated) motive was something like “it is the natural order of things that capital flows downhill, so let’s put the plant in India, not China.”

A variant of this argument is that ULC-arbitrage is directly linked to insufficient domestic demand and wage repression, with this last defined as “wages not rising as fast as productivity.” A moment’s reflection based on an undergraduate acquaintance with Marx would suggest that this is also known as “surplus value,” and not just a defining feature of capitalism but also one found across a variety of trade balance profiles. Indeed, some research from the OECD suggests that the wedge between wages and productivity is practically universal and also that the size of the wedge does not necessarily always correspond to either the size or the sign on the trade balance.

As to the argument that emerging markets SHOULD be running trade deficits in a world-run-right, I have a “and how did that usually work out for the ones that tried that in the last 50 years” rejoinder here on the different ways that EM get into trouble. The bottom line is that under the current configuration of the international monetary and financial system, it is entirely rational for EM countries to pursue the kind of balance of payments resilience that comes from limited external debt, reserve accumulation, and an export-mix that responds very fast and positively to a cyclical weakening of the exchange rate. In other words, to do the kind of thing at which Foroohar and Pettis look askance.

Much of the above is academic because the answer to the biggest trade question in the real world right now—will the US and the EU respond to a jump in Chinese production and exports of Electric Vehicles with (more) restrictions and tariffs—is almost certainly yes. Given the potential costs to the cause of environmental sustainability, this would be a controversial choice, as many in the US have argued here and here. Still the politics of the decision seem to lead here inevitably, even if some of the arguments about how this is the correct response to a systematic preference for investment over consumption don’t pass my personal smell test. I would note that there are many other cases of subsidies for domestic production in excess of domestic consumption that necessarily needs an outlet to external markets, in turn disincentivizing domestic production among importers — agricultural subsidies in the US, the EU and China all fit that bill (in China the damage from massive import substitution in cotton hits poor exporters).

Further, we have seen other recent compositional shifts in global trade balances and attendant financial distress driven by sudden increases in the output of a key product, initially driven by sizable investments that lost money, and yet these have been treated as an unalloyed good in most North Atlantic commentary. In a recent post, I wrote about this (and other things) more extensively, but I think it worthwhile to repeat what I said there:

If one thinks that the shale revolution was a positive supply shock that benefited the global economy in aggregate, even at the expense of incumbent exporters, then China’s rapid ascent in producing technologically advanced capital goods at lower prices should look similar. Like shale, it is a terms of trade shock that benefits importers (who outnumber incumbent exporters). There are obviously immense political and (potentially) geopolitical difficulties that follow from this, but it seems to me consistent with the logic of spillovers laid out above.” And to return to the present note, the difference between the most common reaction to North American shale and to Chinese EVs might just be an (entirely understandable) case of “yes, but we were doing it before; this time, it’s happening to us.

I’m close to wrapping up here, so I should note that I am unambiguously in favor of a vastly more expansive Chinese safety net, hukou reform, and stepped-up efforts to speed up income convergence between coastal and interior provinces. But I also think that these efforts are entirely consistent with efforts to increase technological convergence with the rest of the world (and the periodic sorpasso as seems to have happened with EV).

And while I am sympathetic to catch-up growth, I have been considerably more acerbic about Germany’s fiscal course both at home and in the Eurozone at large. I have suggested that an inevitable (and serial) consequence of German efforts to combine trade surpluses with fiscal restraint at the level of both the country and the Eurozone at large is an infamous history of stupid lending decisions by its financial institutions. I also have a rude joke that the infamous tweet in fantastically bad taste by the German finance ministry about its zero-deficit fetish makes it The Night Exporter. But my point here is that in that both cases, I think of the goal as a fiscal policy that leads to better domestic (and in the case of Germany, neighborhood) outcomes, rather than a search for balanced trade in and of itself. The latter might come, but even if it doesn’t, it’s fine as long as the better fiscal outcomes are achieved.

There are places that have supply and places that have demand; places that are capital constrained and places that have capital to go; places that are at the technological frontier, and places that are trying to reach or surpass it. It is better to allow those processes to continue than to tie the world to a shibboleth of getting as close to national self-sufficiency as possible.1

Whew. I just had to get that off my chest.

This damn essay is cited approvingly everywhere these days and it drives me crazy. It should be perfectly obvious to anyone with even a rudimentary knowledge of history and the economic geography of the British Isles that when Keynes wrote it in 1933, he obviously meant Imperial Self-Sufficiency.