Most Favoured Nation: Safeguarding Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland Protocol problem, 3D printing and attempts to automate me out of a job

Welcome to the 60th edition of Most Favoured Nation. This week’s edition is free for all to read. If you would like to receive top quality trade content in your inbox every week, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber.

In the first ever edition of Most Favoured Nation I wrote about the complicated interaction between the Northern Ireland Protocol and the EU’s Trump-era steel safeguard tariffs. So what better way to celebrate the 60th edition of MFN than to return to the topic, which was kinda fixed but is now kinda broken again.

First, let’s recap.

From a UK trade policy perspective, the Northern Ireland Protocol is, well, rather complicated. For exports, no problem. Goods exported from Northern Ireland are UK goods, and are treated as such for the purpose of UK free trade agreements and the like. But when goods are moved into Northern Ireland, from Great Britain or the rest of the world, whether they are treated as entering the UK or EU customs territory depends on a number of factors.

In the event the UK’s applied tariff is lower than the EU’s, the UK tariff only applies if the importer is registered under the Protocol’s “not at risk” scheme (to ensure the import doesn’t end up south of the border) *and* the difference between the applied UK tariff and the applied EU tariff is less than 3% [Article 3, 1, (b), (ii)].

Things get even more complicated if you are importing a product subject to a trade defence measure, which, under the Protocol, is automatically considered as being at risk of onward movement into the EU and therefore not eligible for the UK tariff.

AND things get even even more complicated if the EU safeguard incorporates tariff-rate quotas, due to a bizarre unilateral decision in 2020 to specifically prevent importers in Northern Ireland from making use of EU tariff-rate quotas … for some reason.

All of this means that, in practice, companies importing steel into Northern Ireland are subject to the EU’s tariff regime, but also cannot make use of the EU’s safeguard quotas which would allow a set quantity of steel to avoid the 25% safeguard tariff. So a 25% tariff is applicable (at least in theory … the UK was never exactly particularly compliant when it comes to this …)

Anyway, this originally was even even even more complicated when you consider that a 25% tariff should also therefore apply to steel moving from Great Britain to Northern Ireland, due to the steel being considered at risk of onward movement (so unable to be treated as remaining in the UK), unable to make use of the EU’s country-specific quota that otherwise applies to steel imports from the UK (because EU TRQs cannot be used by Northern Irish importers), and cannot qualify for zero tariffs under the EU-UK Trade and Co-operation Agreement (the TCA does not supersede trade defence measures).

Thankfully, this was one of the things that Michael Gove, in his brief stint in charge of the implementation of the Brexit deals, kinda sorted out. (See page 4 of Maroš Šefčovič’s letter to Michael Gove). For now, any steel moving from Great Britain to Northern Ireland can do so tariff-free, so long as the steel TRQs the EU applies to imports from the UK remain unfilled. Which is a fairly big caveat.

[If you’re still with me … thank you.]

And this approach was all kind of working … until now.

In June, following a review of its steel safeguards, the EU decide to tweak the associated TRQs slightly to take into account the post-Russian-invasion-of-Ukraine reality.

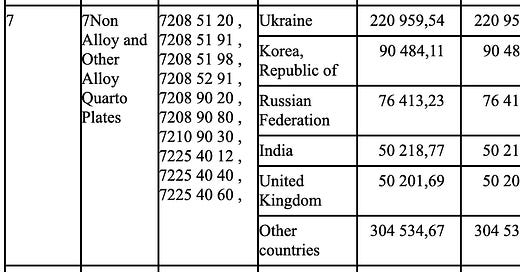

In order to give EU steel importers more flexibility, in a couple of instances (category 7 and 17) the EU has scrapped the country-specific quotas for the UK and others, instead folding them into a wider “other countries” category.

Compare and contrast: EU 2021 steel safeguard allocation

With: EU 2022 steel safeguard allocation

So why does this matter?

Well, whereas before the UK had access to its own country-specific quota, which it could rely on to accommodate steel moving from Great Britain to Northern Ireland, now these movements would be covered by the “other countries” quota … which **could** fill up much more quickly, given the entire world has access to it. Once it is full: 25% tariff on steel moving from Great Britain to Northern Ireland.

So what’s the solution?

The obvious one would be for the EU to either create a bigger quota for the UK, to take into account the intra-UK movements of steel from Great Britain to Northern Ireland … or if it doesn’t want to do that it could even create something Northern Ireland specific.

But the EU doesn’t want to. As part of the review, the EU addressed this issue and said:

Which is unideal.

Anyhow, I reckon that this is something that could be resolved fairly easily if the EU-UK relationship was in a better place. But it’s not. So in the meantime steel safeguards/TRQs are yet another thing for the EU and UK to argue about … even if both parties know that the UK is never ever going to actually apply a 25% tariff to steel moving within the UK, no matter what the law says [in my opinion].

Three Dimensional Trade

In any discussion about deglobalisation or onshoring or the like, at some point someone will say something like “and new technologies such as 3D printing could lead to more localised manufacturing.” Which intuitively makes sense. (I have absolutely been a person saying this in the past.)

But what does the evidence say?

So far … according to this new paper in the Journal of International Economics, there is no evidence to suggest 3D printing will shorten supply chains and reduce trade.

Well.

Time to Automate MFN

On the subject of cool new tech that is going to steal our jobs, a couple of my Flint colleagues engaged a language generating machine model in an attempt to automate me.

They gave it the prompt “Sam Lowe on trade barriers to UK fishing.” This is what my machine-self pumped out:

I am very concerned about the impact of the UK leaving the EU on the fishing industry in the UK. There are a number of barriers to trade in fish and seafood that could have a significant impact on the industry. The most significant barrier is the requirement for a licence to export fish and seafood products to the EU. This could lead to a significant decline in the number of fish and seafood products that are exported to the EU, and could have a major impact on the industry in the UK. I am also concerned about the impact of the UK leaving the EU on the quota system for fishing. The UK currently has a quota of fish that it can catch in EU waters, and this quota is set by the EU. If the UK leaves the EU, it is possible that the UK will no longer have a quota, and this could have a major impact on the fishing industry in the UK.

Now I know what you’re thinking: a MASSIVE improvement on my usual trade guff. And with that, I would like to announce that future MFNs will be fully automated.

As ever, do let me know if you have any questions or comments.

Best,

Sam