Sticking with last week’s theme of trade defence investigations, next week (probably Wednesday) the EU should be releasing the provisional findings of its anti-subsidy investigation into China-origin EVs.

This means we should find out whether any new anti-subsidy tariffs will be applied (let’s assume yes) and if so, how high the tariff(s) will be.

Trying to guess how big these tariffs will be is quite a fun game, given it’s not particularly straightforward.

DG Trade’s enforcement Tsar, and new recipient of France’s Légion d’Honneur (congratulations!), Denis Redonnet will need to consider …

The Evidence. A few weeks ago the US announced it will slap an arbitrary additional 100% tariff on imported Chinese EVs. Biden can do this because the US doesn’t care about complying with international trade rules and is mainly concerned with the domestic imperative to look tough on China in the run-up to an election. The EU doesn’t have the same luxury/inclination. The level of the EU anti-subsidy tariff on the individual firms included in the sample will need to be supported by a credible evidence base, which will pull them down quite a lot. This is because China will probably challenge the EU tariffs, as is its right, and due to both the EU and China being members of the MPIA, an alternative to the broken WTO appellate body, the EU could end up losing. [As an aside, compared to the other retaliatory options, discussed below, China bringing a WTO case that ends up at the MPIA is probably a best-case outcome from an EU perspective … so long as it wins, or at least doesn’t lose in an embarrassing way.]

The impact. Like, will they work? As reported everywhere, the Rhodium Group published a paper arguing that anti-subsidy duties of 40-50%, or higher, are probably needed if the EU truly wants to shut Chinese firms out of the EU market. Given shutting out completely isn’t the EU’s objective, this estimate probably provides us with the ceiling. However, I would be amazed if the default applied tariff is anywhere near this but don’t rule out one of the sampled companies getting close.

Retaliation risk. In the run-up to the EU announcement, China has been ramping up the threats to retaliate against (mainly) EU agricultural exports. I view this largely as an effort to keep the tariffs down, rather than see them off completely, but again, it provides another reason for the EU to be cautious.

Member-state divisions. Some member states (France) are more enthusiastic about tariffing Chinese EVs than others (Germany). The provisional duties will soon need to be signed off officially by the EU member states, so you need to find a level that keeps everyone happy, or at least not overly sad.

Unintended consequences. What happens next? Assuming China-origin vehicles become less competitive in the EU, do Chinese firms start shipping them in from other countries? Do they start investing more heavily in EU-located production facilities? Does the EU want that? Does this mean new investigations, either at home (foreign subsidies regulation) or abroad? Does this ever end?

I’ve probably missed some, but taking into account all of the above, I reckon the standard guess of a default tariff somewhere in the 10-20% range (on top of the existing 10%) is about right. But I wouldn’t be surprised if one or more of the sampled firms is hit with a company-specific tariff that is higher. Let’s go for … a total of 37.5% (10+27.5).

Tune in next week to find out whether I was spectacularly right, in which case I will link back to this post, or spectacularly wrong, in which case we shall never speak of it again.

CBAM risk

I am fairly confident that once the EU CBAM gets fully up and running — importers will have to start paying from the beginning of 2026, although I wouldn’t be surprised if this deadline gets pushed back – the EU will come under immediate pressure to extend CBAM’s coverage to capture more downstream production.

The reason I say this is because the EU CBAM, as currently designed, inadvertently incentivises the offshoring of downstream production.

For example, if you make washing machines in the EU, CBAM means your input costs (steel, aluminium) have possibly gone up because it has become more expensive to import carbon-intense steel. However, if you make washing machines outside of the EU and then export them to the EU, you can still use carbon-intense steel without being hit by the CBAM penalty.

With thanks to the friendly MFN subscriber who pinged this it to me, a new report by Sandbag reiterates this point as one of its key findings, with two case studies, one on cars, and one on wind farms:

Example 1: an offshore wind farm

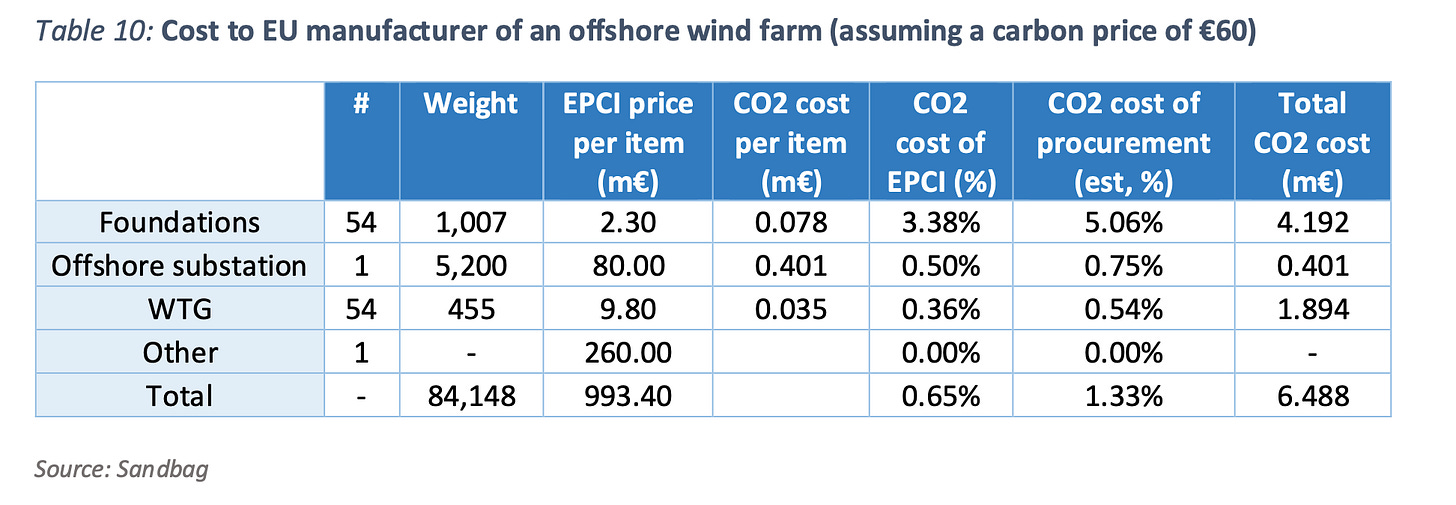

This paragraph analyses potential effects on the real-life example of an offshore windfarm which was built in the North Sea. The total budget for the final client for this 300+MW wind farm comprising 54 wind turbine generators (WTG) was €1bn, of which most was for the EPCI contracts (Engineering, Procurement, Construction and Installation) of the farm’s main elements.

All the main elements were manufactured in the EU, where steelmakers receive free CO2 permits. If those free permits were removed as the CBAM enters into force, and carbon costs were passed through to the final product, it would cost more to manufacture wind farms in Europe than currently, which could comparatively benefit suppliers based overseas.

Table 10 shows that a carbon price of €60, if the carbon costs were passed through to the client as described in the previous section, would raise the overall price by 0.65%, which would probably not materially affect the demand for EU-made wind farms overall. However, one of the farm’s elements could suffer from overseas competition: EU-made foundations (i.e. sets of two long tubes called ‘monopiles’ and ‘transition pieces’ screwed together) would become 5.06% more expensive. Given the very specific transport conditions of these elements, it is unlikely that those would be sourced from remote areas, so the risk of carbon leakage related to this product seems however limited

Chart of the week

I contributed in a very small way to a new UK in a Changing Europe Report looking at the state of UK Trade, which you can find here.

Of the many excellent charts, I particularly liked this one:

Best,

Sam