The big trade news is that (as predicted) Canada has decided to follow the US and EU (but mainly the US) and slap high tariffs on imported Chinese electric vehicles:

… the Government of Canada intends to implement a 100 per cent surtax on all Chinese-made EVs, effective October 1, 2024. This includes electric and certain hybrid passenger automobiles, trucks, buses, and delivery vans. This surtax will apply in addition to the Most-Favoured Nation import tariff of 6.1 per cent that currently applies to EVs produced in China and imported into Canada.

In addition, Canada is going to apply a 25 per cent tariff on imported Chinese steel and aluminium, launch a 30-day consultation on applying tariffs to other sectors such as batteries, battery parts, semiconductors, solar products, and critical minerals, and, most interestingly, make it more difficult for EVs made elsewhere to qualify for Canadain subsidies:

… the federal government is announcing its intention to limit eligibility for the Incentives for Zero-Emission Vehicles (iZEV), the Incentives for Medium and Heavy Duty Zero Emission Vehicles (iMHZEV), and the Zero Emission Vehicle Infrastructure Program (ZEVIP) to products made in countries which have negotiated free trade agreements with Canada.

The slight shock isn’t that Canada has imposed tariffs, it is that it has, unlike the EU, decided to go full Trump/Biden and disregard trade rules entirely and follow the US’s approach to the letter.

Politically, this probably makes sense — Canadians tell me the measures could be popular domestically and they, possibly, premetively put Canada in Trump’s good books. But if you care about the rules-based trading system … less good.

In terms of the G7, this leaves the UK and Japan as outliers on the China EV tariffs issue.

We discussed the UK response a little in last week’s edition of MFN, but one other point that is slightly under-discussed is that, in contrast to its G7 contemporaries, the regulatory set-up of the UK’s EV market is structurally reliant on the import of Chinese EVs.

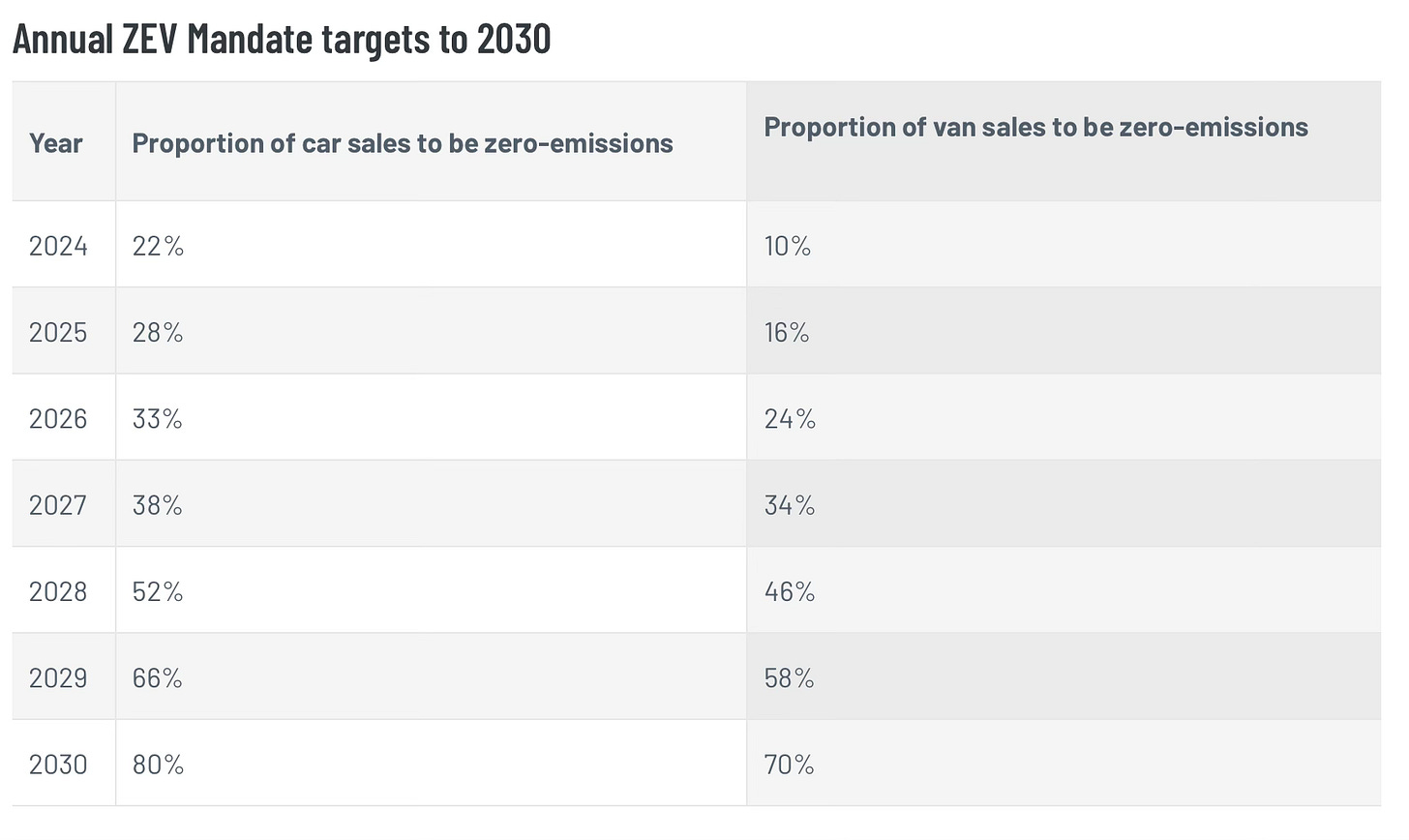

In summary, from January 2024 car manufacturers will be required to meet sales targets for zero emissions vehicles, the so-called ZEV Mandate:

Manufacturers that do not hit these targets will be fined £15,000 per non-compliant car and £9,000 per van (ultimately rising to £18,000).

To account for the fact that lots of carmakers won’t hit these targets, in the early years of the ZEV mandate they will be able to trade ZEV credits.

This means that a manufacturer who easily clears its ZEV mandate target will be able to sell their excess credits to those who haven’t. This allows the scheme to be successful on aggregate, even if individual carmakers are decarbonising their offering at different rates.

What does this have to do with China?

Well, in practice, lots of the traditional carmakers with a decent market share in the UK are not going to meet these targets. So they are going to need to buy some credits.

Who to buy from? That would be companies that sell exclusively EVs (and therefore easily exceed the targets). In practice, this means Tesla and, well, newer Chinese brands.

The need for ZEV credits therefore creates a de facto incentive to allow new Chinese EV entrants into the market.

The scheme design, at least in its early days, also functions as a de facto cross-subsidy to Tesla and the Chinese EV firms, with legacy European (and other) companies forced to pay them money in exchange for credits.

Anyway, given that everyone else [other than the EU] is breaking the rules, and the Labour government likes the idea of local jobs for local people I wonder if we might see some discussion about the UK fiddling with the ZEV mandate to make it slightly more favourable for local producers.

Supply Chain Risk

Do have a listen to the latest episode of Credit Notes, a podcast series I moderate for AIG.

In the most recent episode, I chat with Julian King, the former EU Trade Commissioner for the Security Union and Alicia García-Herrero (Substack here), the Chief Economist for Asia Pacific at French investment bank Natixis about the concept of trade overdependency. What is it? Does it actually exist? Can trade be weaponised? Etc.

Over the course of the conversation we cover 5G, semiconductors, Russia, Taiwan, you name it. And Julian and Alicia are very thoughtful, even if I’m not.

You can either listen to it here, or at a podcast provider of your choosing.

Report of the week

On a similar topic, and with thanks to Simon Evenett for flagging on LinkedIn a new paper by analysts at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York has attempted to quantify the costs of US export controls.

Here’s the abstract [emphasis added]:

Amid the current U.S.-China technological race, the U.S. has imposed export controls to deny China access to strategic technologies. We document that these measures prompted a broad-based decoupling of U.S. and Chinese supply chains. Once their Chinese customers are subject to export controls, U.S. suppliers are more likely to terminate relations with Chinese customers, including those not targeted by export controls. However, we find no evidence of reshoring or friend-shoring. As a result of these disruptions, affected suppliers have negative abnormal stock returns, wiping out $130 billion in market capitalization, and experience a drop in bank lending, profitability, and employment.

And here’s the paper: Geopolitical Risk and Decoupling: Evidence from U.S. Export Controls.

Chart of the week

On a similar topic [again], a new report by Mary E. Lovely and Jing Yan of the Peterson Institute takes a look at trade dependencies and produces this great chart:

Best,

Sam