Earlier this week, Donald Trump signed a ‘Proclamation’ imposing an additional 25 per cent tariff on all passenger vehicles (sedans, SUVs, crossovers, minivans, cargo vans) and light trucks that have not been built in the United States.

The 25 per cent tariff also applies to key automobile parts (engines, transmissions, powertrain parts, and electrical components). (Note: this coverage may be extended in future.)

The tariff on automobiles will enter into force on 3 April 2025. The tariff on automobile parts will enter into force no later than 3 May 2025.

However, while there are no explicit exemptions [as of yet] for vehicles exported to the US from Canada and Mexico, the tariff isn’t necessarily 25 per cent.

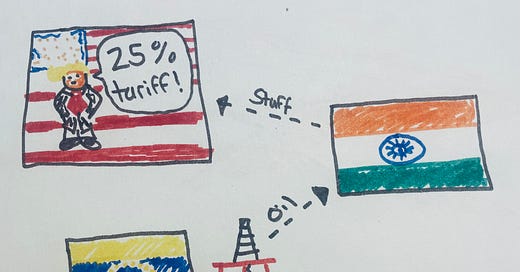

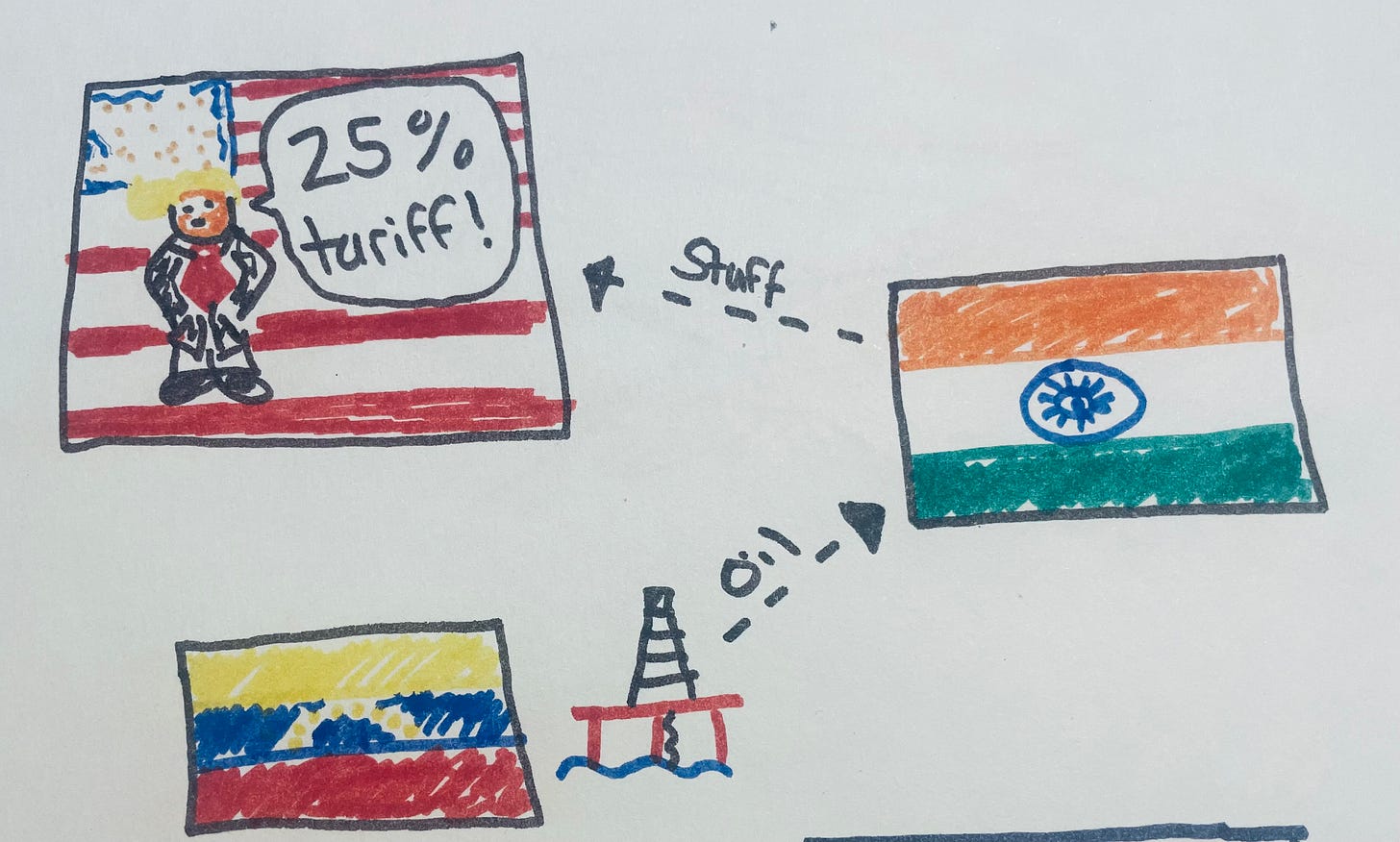

This is because the proclamation stipulates that if an automobile qualifies for preferential treatment under the US, Canada, Mexico free trade agreement (USMCA), the tariff may only apply to the non-US content of the vehicle.

This is all subject to the importer jumping through some administrative hoops and shall be calculated by subtracting the value of the US content in an automobile from the total value of the automobile.

The impact? Carmakers with a large North American footprint will face differential rates when exporting final vehicles into the US from Mexico/Canada.

For example, if we assume that a car imported from Mexico/Canada under USMCA has 40 per cent non-US content, under the new protocol the effective tariff rate on the whole vehicle would be 10 per cent.

If, under a similar scenario, the vehicle has 50 per cent non-US content, the effective tariff rate on the whole vehicle would be 12.5 per cent. Etc.

In infographic form1 [note: thank you to those on Bluesky who critiqued an earlier version of this masterpiece]:

If this broad approach sounds eerily familiar, that’s because it is.

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about how the US is applying tariffs to the steel and aluminium content of downstream products, such as sports equipment.

… it turns out that the 25 per cent tariff can, in some instances, apply exclusively to the steel/aluminium content of a product rather than the product’s total value.

See this US Customs and Border Protection Guidance (emphasis added):

Reporting Instructions for Duties Based on Steel Content

For new steel derivatives outside of Chapter 73, the 25 percent duty is to be reported with HTS 9903.81.91 based upon the value of the steel content.

If the value of the steel content is the same as the entered value or is unknown, the duty must be reported under HTS 9903.81.91 based on the entire entered value, and report on only one entry summary line.

If the value of the steel content is less than the entered value of the imported article, the good must be reported on two lines. The first line will represent the non-steel content, while the second line will represent the steel content.

This means that if the cost of your imported derivative product is $100, but the steel content is only valued at $25, the ultimate tariff would be 25% of $25 rather than 25% of $100. Assuming you can be bothered to do all the paperwork that is.

I then wrote [emphasis added], which, after all this, looks increasingly plausible:

Anyhow, this approach makes me wonder if we might see something similar elsewhere.

For example, what if you were tariffed based on the Chinese value of your imported product?

For example, a European EV battery would normally be subject to a 3.4% US tariff. But what if the European EV battery’s China-originating cells (subject to a 25% tariff), account for 70% of the value?

Assuming the battery costs $1000, you could imagine a situation in which the US started asking importers to pay a 3.4% tariff on the EU value and a 25% tariff on the China content. [Assuming the alternative is to pay the full China tariff.]

This would result in a total tariff cost of ($300*0.034)+($700*0.25)] $185.2 rather than [$1000*0.034] $34.

It would also be MASSIVELY complicated and costly for firms. This makes me think it is exactly the type of thing this US administration might try to do.

Whoops.

Anyhow, one final point:

The proclamation confirms that these tariffs are in addition to existing tariffs and duties. Pretty much all of the Trump interventions so far have stipulated this, but for some reason it goes largely unremarked on.

This means, for example, that the actual tariff applied to light trucks imported from, say, the EU will be 50 per cent — the existing 25 per cent chicken tax plus the new 25 per cent tariff.

This also means that you can play a fun game called “let’s add up all the tariffs to get a really big number”.

For example, Chinese electric vehicles already face an MFN tariff of 2.5 per cent, a Biden-era additional 100 per cent tariff, the new China-specific 20 per cent tariff, the risk of a new Venezuela-related secondary 25 per cent tariff (more below), and now the new 25 per cent auto tariff. If my calculator is serving me correctly, this means a potential total tariff of 172.5 per cent.

In meme form:

Creative coercion

One of the standard Trump assumptions has been that he will threaten countries with tariffs if those countries don’t support him in his international endevours.

For example, I wrote this for FT Alphaville last November:

I assume the conversation with lots of countries, including those scoring below 0 on the MAGA index, will go something like this: “As well as buying more stuff from us, if you want to avoid the universal tariff you need to impose high tariffs on Chinese imports”.

This will create a dilemma for the UK, EU and others. Assuming that China would retaliate to any blanket tariffs, countries will forced to choose between the US blanket tariff and the Chinese retaliatory tariffs. In practice it probably won’t be quite so binary, and countries may try to placate Trump with commitments to impose tariffs they were considering anyway.

For example, the EU has already imposed anti-subsidy tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, as well as lots of trade defence tariffs covering products such as steel, bikes, graphite, biodiesel and others, so may try to placate him by initiating new investigations into products such as EV batteries, solar, and wind turbines.

Well, it turns out that this was in fact the vanilla version and in fact Trump will be “quite so binary”.

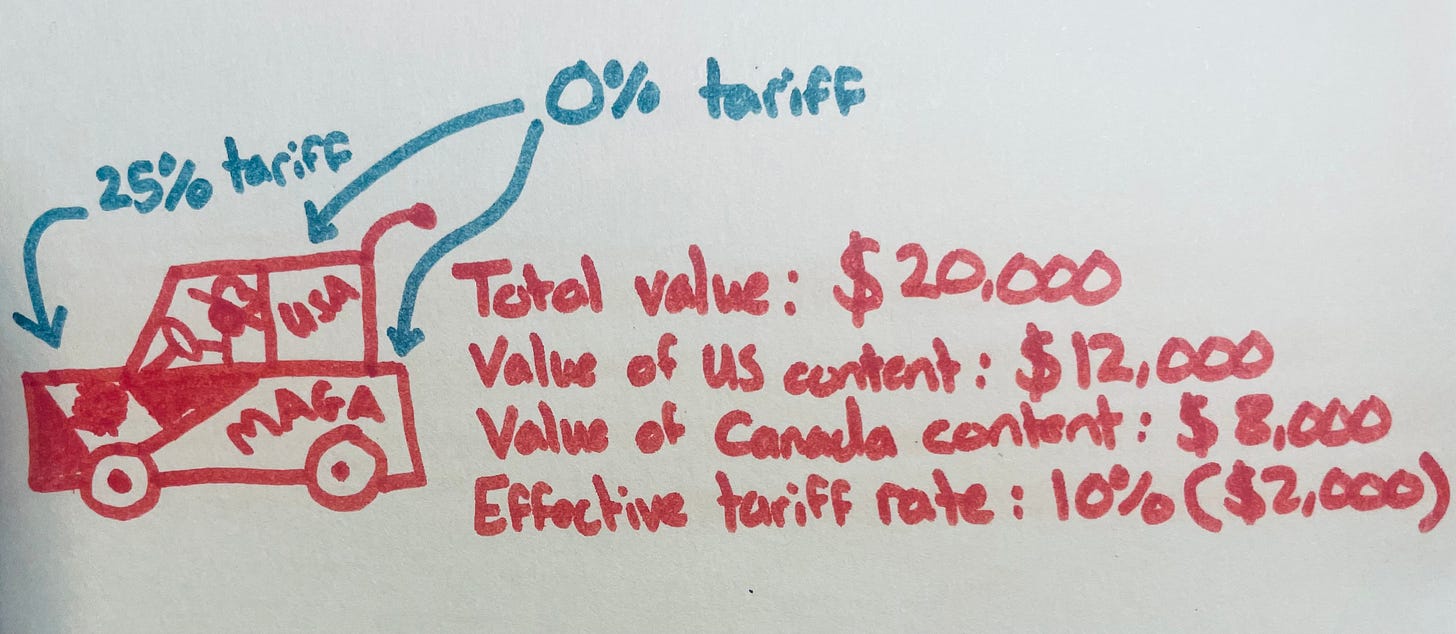

By which I mean he has signed an executive order granting the US Secretary of State the power to impose a 25 per cent tariff on any country that imports oil from Venezuela.

In Infographic form:

And … on the assumption you really want to destroy another country’s economy through coercive means … it’s kinda clever?

But where does it end?

A 25 per cent tariff if you continue to buy Chinese Electric Vehicles?

A 25 per cent tariff if you continue to buy French cheese?

A 25 per cent tariff if you continue to buy Greenlandic fish?

A 25 per cent tariff if you continue to buy Taiwanese semiconductors?

Hmmm.

Wood

Oh, Trump’s also said he is going to apply more tariffs to imported Canadian lumber and lumber derivatives for national security reasons. I think this is because he is afraid of Mark Carney’s … war cabinet.

Have a good day!

Sam

Some caveats: It is not at all clear in the context of this USMCA-specific provision whether the US content will be 0 per cent (as per USMCA) or 2.5 per cent (as per MFN), and, in turn, whether the non-US tariff would be 25 per cent on top of 0 per cent, or 25 per cent on top of 2.5 per cent (ie 27.5 per cent)